As a child, I spent my summers playing in the tidal areas of Tybee Island near Savannah, Georgia. When I moved to Florida, it was like coming home to an ecosystem I loved and missed. Florida’s rivers, barrier islands, springs, and ocean waters are our wilderness, and my husband Kevin and I spend as much time as possible exploring the waters by SUP, kayak, and sailboat. I have kayak camped in the Keys and the 10,000 Islands, surfed my kayak in the Atlantic, and recently learned to SUP surf. We are longtime volunteers with Paddle Florida. Even though Florida is blessed with what looks like an abundance of water, its rivers, springs, and aquifer are threatened by pollution and over-consumption, among other things. So while I enjoy playing and surfing, I also work to protect Florida’s waters.

Confessions of a Senior Grom

My first day surfing in Costa Rica—I’m up and flying down the biggest wave I have ever ridden. The locals consider this flat, but these clean waves impressed us Floridians with their size and power. I never asked how big they were. But there we were—surf camp in Dominical, Costa Rica.

As a newer surfer, I assumed both that I would use a soft-top board and that I would surf in the whitewater, or broken waves. No to both. I was nervous and excited that I would be paddling out to the green waves on a hard board. The waves of Dominicalito, a protected cove, are ideal for beginners and intermediates. Ami Berg, owner of Central Florida Women Surfing, coordinated our trip with Debbie Zec, owner of the Dominical Surf School and herself a Dominical native.

Everyone improved over our 5 days of surf lessons. I was impressed by the level of instruction, both the on-water feedback and the video analysis. My goals: getting up faster and initiating turns. Each day, I focused on the pointers Gonza, my primary instructor, offered and watched the others. In the evening, we brainstormed with Ami and did the surf dance—the twist, compression and extension that help turn the board. Land practice helps because everything in the durf happens quickly. The ocean gives instant feedback.

Surf and surf culture has long fascinated me, but I wondered if my window hadn’t closed. I had kayak surfed and SUP surfed and had my eye out for an opportunity to try board surf. About 2 years ago, I booked a beginner lesson with Ami at Central Florida Women Surfing in Daytona Beach. It was a windy, choppy day, and the paddle nearly killed me, but I was hooked.

I came back again and again, a senior grom, a term usually applied to children learning to surf. I also discovered the Wahine Kai Surf Club, St Augustine chapter, and met Beth Masters of Salty Sistahs Surf School. Through these groups, I made friends, developed skills, and learned how not to be a kook, a derogatory term for one who violates surf norms. Surfing is great, but these friends and communities have made it so much richer.

I obsessed over surf videos on Instagram and read whatever I could as I tried to suck less at surf. In her book (It’s great to) Suck at Something The Unexpected Joy of Wiping Out and What It Can Teach Us About Patience, Resilience and the Stuff That Really Matters Karen Rinaldi uses surfing and guitar (another skill I am working to suck at) to explores the benefits of sucking at new skills. Further, she notes, the public nature of surf promotes humility and the ability to laugh at yourself. Some say that the best surfer is the one having the most fun. I’ve never walked out of the ocean without smiling.

Our surf sessions were exhilarating but exhausting. Paddling out through the break is harder than simply jumping on the board and riding whitewater, but so much more fun. I was often out of breath when I reached the outside, but I learned to time the waves and turtle-rolled when a set rolled through. The clean, well-timed sets are unlike Florida’s generally messy conditions, and I experimented with smaller and more performance-oriented boards. Nonetheless, my first post-trip surf session in St. Augustine was a reality check—washing machine conditions and a wetsuit. But so fun.

After surf, we returned to our hotel Villas Rio Mar, floated in the hotel pools, and explored Dominical. The dirt road into Dominical ran along the Rio Baru which, we were assured, had no crocodiles. Local families swam in the river so we felt safe swimming across the river to use the rope swing. Dominical maintains the feel of a small fishing village, and the residents are working to preserve that vibe. Monkeys and iguanas roamed freely, and toucans flew overhead, literally a tropical paradise.

Over the week, we did yoga, had massages, hiked to a waterfall, and wandered the town. This time gave us the luxury of extended conversations, and we talked about our lives, jobs, and relationships, and, of course, surf. Our group bonded, and I left with real friends, a real benefit of a trip like this. Our grand finale— a sunset bonfire on Dominical Beach where surfers shred massive waves far beyond my comfort level.

I don’t know where this surf journey will lead, and I never imagined it would bring me here. I wouldn’t have gotten this far without the friends I’ve made. So I’ll hang on for the ride and trust that friends, new places, and a return to Dominical will follow. And next time, I expect to see a sloth in the wild.

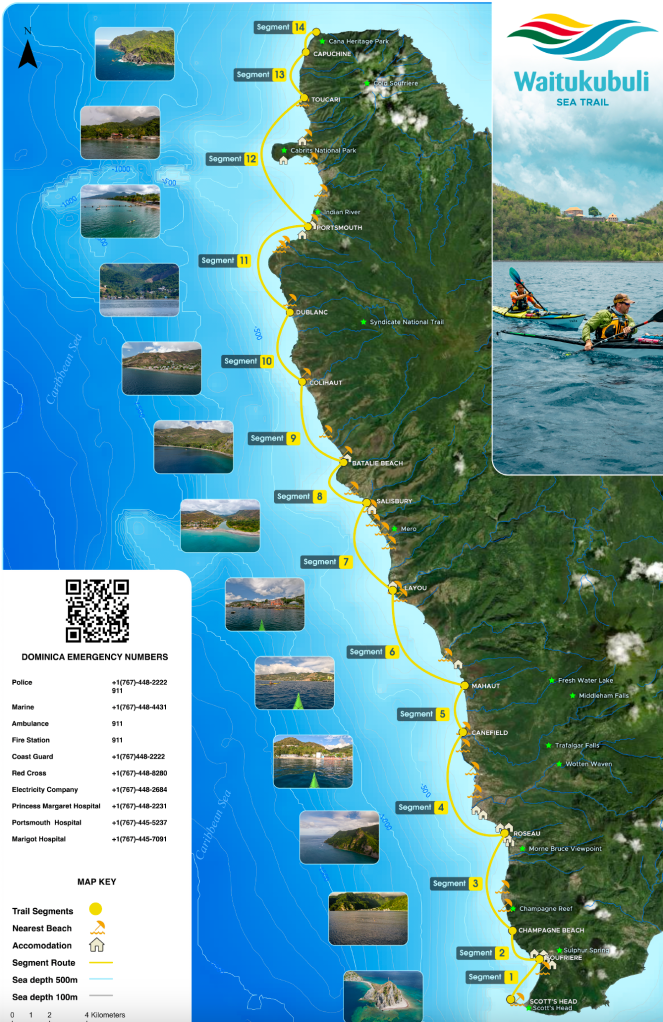

Paddling Dominica’s Waitukubuli Sea Trail

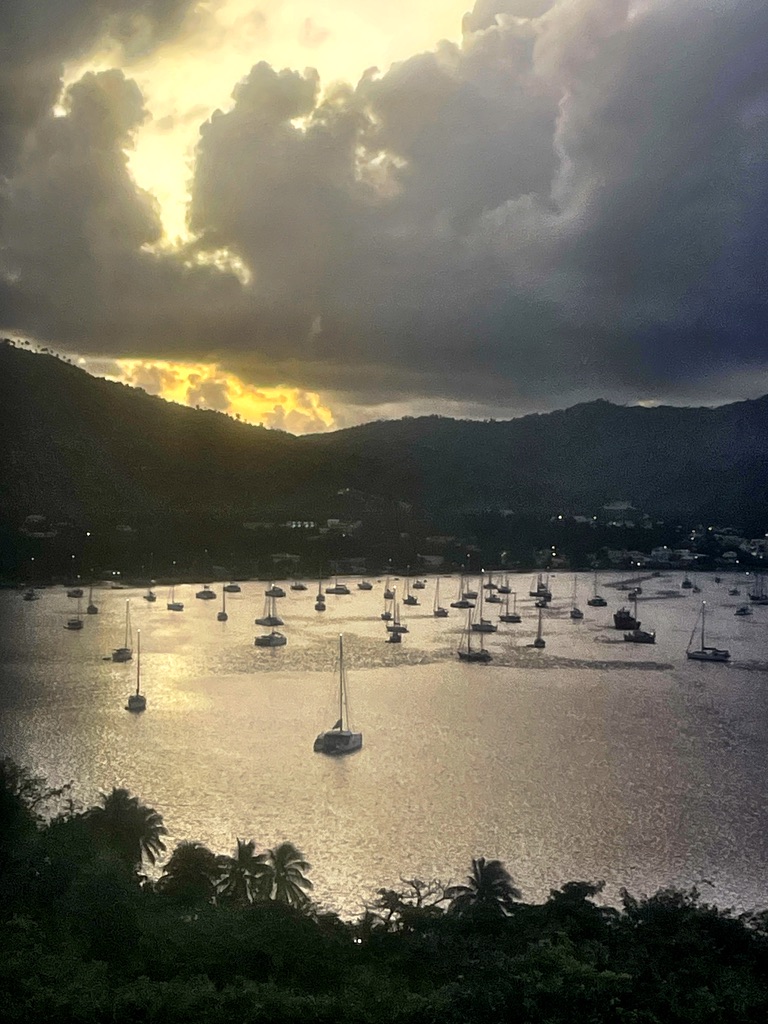

Explore Dominica by kayak? Try the Waitukubuli Sea Kayak Trail, a 40-ish mile paddle trail down Dominica’s stunning western coastline. For years, Dominica’s rugged landscape and range of outdoor activities had intrigued me, and when Michael Gray of Uncommon Adventures organized this trip, I jumped in. Finally March 2024 arrived, and we were on our way.

Before we met our group from Uncommon Adventures, several of us spent one night at the Jungle Bay Resort, and we agreed that one night was not enough. Their wide range of outdoor activities demands a return trip.

The next day, we arrived at the Soufriere Outdoor Centre, only a short and steep drive from the Jungle Bay Resort. Wes Moses started the Soufriere Outdoor Centre and, with his Dominican colleagues, established the Waitukubuli Sea Trail which parallels the Waitukubuli Trail through the mountains. After meeting Wes at a Sea Kayak Georgia symposium, I had been following the progress of the guesthouse and trail. Up until now, relatively few have paddled the Waitukubuki Sea Trail, but recent coverage in Travel and Leisure and Youtube should change that. That afternoon, we chose boats and outfitted them for the week. Wes had a wide selection of NDKs (Nigel Dennis Kayaks), and I was fortunate to get a Pilgrim Expedition, a boat I have paddled extensively.

Monday—finally on the water. Michael and Dominican guide Kerry Alleyne led to the southern tip of Dominica, where the Caribbean meets the Atlantic. Michael had warned us about winds whipping through the mountains, but none of us were prepared for the abrupt transition from Caribbean paradise to boat-stopping gusts and back, all in under a minute. The winds dropped as the week went on, but it kept us on our toes.

That afternoon, we snorkeled around Bubble Beach Spa, a black sand and rock beach so named for the bubbles emerging from the volcanic thermal springs. After a day of paddling and snorkeling, Michael’s grilled snapper, rum punch, and Kubuli beer were a welcome treat. And we learned the mnenonic for the trail: Wai-tu-kubuli? Because one is not enough. Noone suffered from hunger or thirst that week.

Tuesday morning, we crammed three days worth of gear and clothing into our boats and headed north, passing Champagne Beach, another bubbly snorkeling spot. Our destination: Anchorage Hotel in Rousseau, Dominica’s capitol. Despite the heat, that afternoon’s trip to the hot springs felt wonderful, as we tested out the different levels of heat in the pools.

The thermal springs prepped us for our longest day, a 15-ish mile trek from the Anchorage Hotel to Sunset Bay’s Lobster Palace. A slight tailwind and following seas made the trip surprisingly fast and easy. We passed several busy ports along the way, and that was the only time we had to watch for boat traffic during the trip. In Layou, just south of St. Joseph, we experienced what I consider to be the culinary delight of the week: Boyd’s Bakes, fry bread stuffed with a curry-infused smoked fish. Boyds Bakes, in itself, is worth a return visit.

Sunset Bay and the Lobster Palace! We dragged our boats on to the beach and settled in for the feast. Noone left the Lobster Palace hungry—we had a three course breakfast!

En route to Fort Shirley, we snorkeled at Secret Beach, one of the best snorkeling spots of the trip.

Thursday night, we reached Cabrits National Park and Fort Shirley, a UNESCO Heritage site and our home for the next three nights.

“Fort Shirley is part of the Cabrits National Park in the north of Dominica and can be considered Dominica’s most important historic site and was the scene of the famous revolt of the 8th West India Regiment in 1802 when African slave soldiers took over the garrison for three days in protest over conditions there and the fear of being sent to work in the canefields. Their action resulted in all slave soldiers in the British Empire being made free in 1807.”

Unfortunately the fort historian, Dr. Lenox Honeychurch, was unavailable that day. I am often struck at the somber histories of areas of great beauty where I paddle and enjoy nature.

Layover day—visit to Free Up Farm and Syndicate Falls.

Segment 14—The End! The Witches Hat marks the northern terminus of the trail where the Caribbean once again meets with the Atlantic. We had completed the Waitkubuli Sea Trail, and it was time to unload our boats and send them back to Wes in Soufriere.

The next morning, the group split, making our way back to the airport. Kevin, Michael, Lisa and I spent the night at the lovely Sea Cliff Eco-Cottages, which also have a gin distillery. Another site worth a return. En route, we saw some promising waves—a surf trip up next?—and the Point Baptiste Estate Chocolate Factory.

Our amazing time in Dominica had come to an end, and I felt like I had only scratched the surface. So much to do, and so much to learn. Our guide Kerry and our driver Kish from Portsmouth had explained so much to us about Dominica, and that left me eager to return. As they say about Kubuli: Why Two? Because one is not enough. And so with Dominica—one week is not enough.

Fort de Soto to Cape HAZE: 62 MILES by SUP

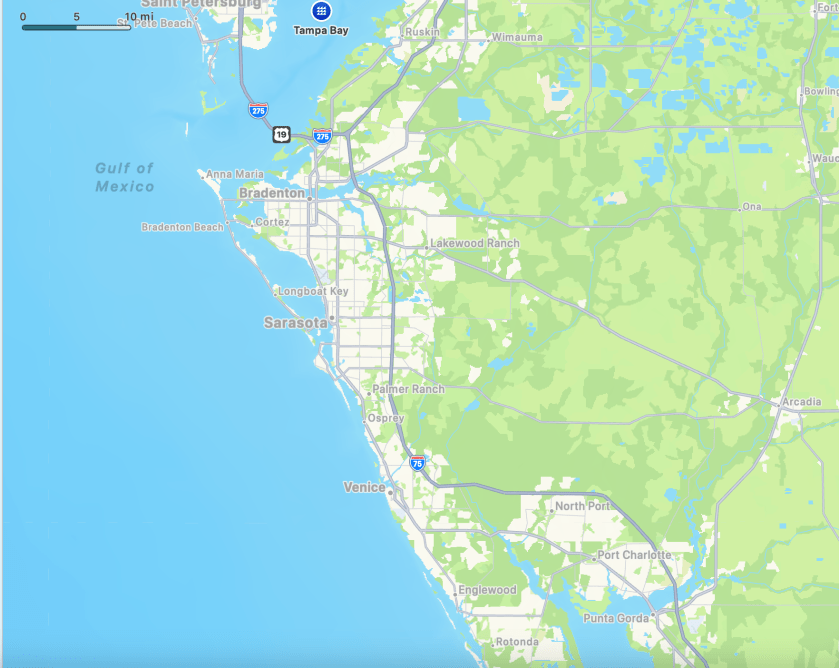

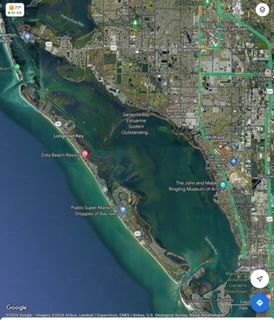

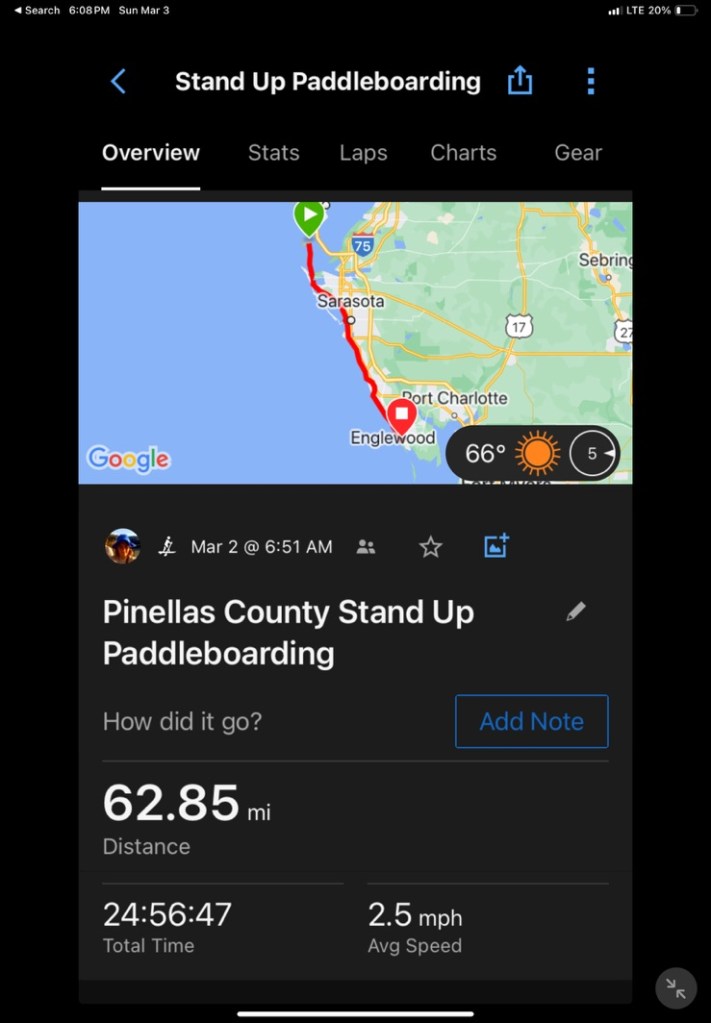

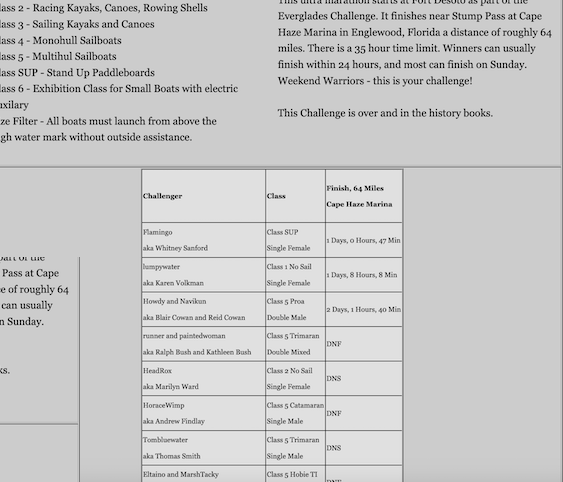

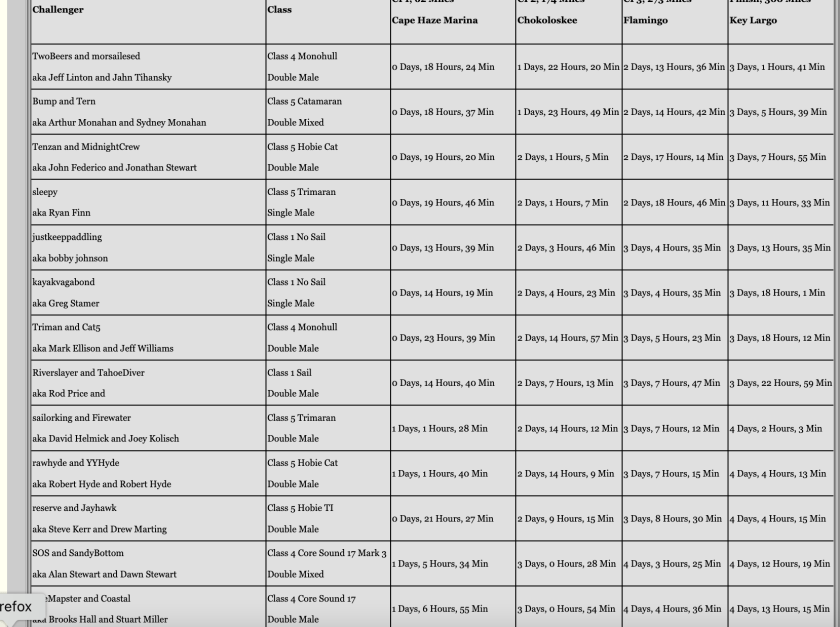

7 am. The horn blows, and I, Flamingo, shoved my paddleboard—a 14′ x 24′ Sic Maui Atlantis—into Tampa Bay. Destination: Cape Haze Marina in Englewood, Florida, 62 miles south, also Checkpoint 1 of the Everglades Challenge. I was not alone. Over 80 boats stretching along Fort de Soto Park‘s East Beach launched en masse marking the start of Watertribe 2024. As part of Watertribe’s Ultramarathon, I had 35 hours to reach Cape Haze Marina. Those in the 300 mile Everglades Challenge had approximately one week to reach Key Largo.

The day prior, we gathered on the beach to set up boats and undergo pre-race inspection. Since participants spend between 1-7 days on the water, we carry a substantial amount of safety/rescue and camping gear as well as food and water. As part of my training, I paddled many miles loaded with gear and practiced getting on and off the board.

We arrived pre-dawn, and I was thrilled to see low winds and calm seas. In previous years, rough weather required a Plan B start, a launch south of Tampa Bay. Everyone was excited for a beach start and smooth crossings of Tampa Bay and Sarasota Bay.

And we’re off! Sailboats charged to the right towards the open gulf; paddlers and smaller sailboats followed the ICW between the mainland and barrier islands. I watched the other boats as we crossed the shipping channel—a huge relief. Light winds and small chop forced me to adjust my angle, keeping me to the west of the others. Beyond Tampa Bay, I saw only one other boat until Stump Pass shortly before the finish.

While Tampa Bay had intimidated me in the past, I should have feared Sarasota Bay. Friends had warned me that Sarasota Bay was shallow and choppy. Surfing the rollers was fun at first. Eventually I fell off, and the board flipped as I climbed on. Not a race highlight. Next year: balance my gear weight better.

Sarasota Bay was long, really long, but I knew that the waterway would narrow and calm as it narrowed on the south end. After a day of relative isolation, I was not prepared for the hellscape that was south Sarasota Bay. Think Waterworld: Churned waters, tour boats racing through the anchorage, and party boats. Florida spring break. At least I got through before sunset.

Somewhere past Little Sarasota Bay and Vamo, darkness fell. I set my Garmin watch on the map/navigate mode so the sun was my sole guide for time of day. With such a long paddle, I didn’t want to obsess about miles and speed since I could only go as fast as conditions allowed. Not knowing the time was freeing but also disorienting.

Near Vamo, I put on my night paddling gear and lights. By this time, the course narrowed, boat traffic fell, and paddling became much easier. At times, I fought tidal currents, and the top of my paddle came unglued, but the calm night time conditions outweighed those inconveniences. I saw some small fishing boats but mostly I was alone on the water on a moonless night.

Just north of Venice, I passed Snake Island where I heard voices, most likely fellow tribers. I paddled on, remembering the advice that you’ll stop if there’s an easy way out. Many tribers paddle or sail through the first night to bank miles for the inevitable weather delays. The Ultramarathon for me was prep for next year’s Everglades Challenge—crossing the bays and paddling though the night were a good test.

I paddled the ditch, a rock-walled channel around Venice airport, sitting on my Crazy Creek chair. Slow, but still progress. It tweaked a different set of muscles, but saved my feet and legs from cramping. I think I dozed off once or twice. Sometime beyond the ditch, I considered camping when I realized it was 4 am, I thought why bother?

I love the meditative aspect of night paddling, but it affected my balance, something I experienced during the Suwannee 230. I had no problem standing on the board, but I couldn’t stand on land without a paddle for balance.

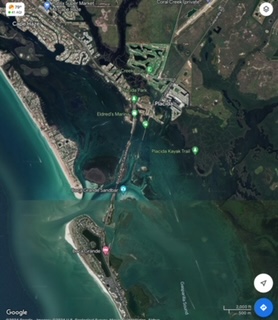

When I reached the dreaded Stump Pass, known for its shifting shoals, three sailboats came though.The first boats I had seen in hours, and we all finished around the same time. I assumed I was dead last, but instead I was first in the Ultramarathon and in the middle of the pack for Everglades Challenge.

I was exhausted but standing. When I checked in, I couldn’t remember the time format which says something. But the hot noodles were restorative, and I enjoyed hearing stories from others as they checked in. Eventually I reloaded the board and paddled several miles south to an anchorage where I met Kevin and KneeDeep 1. The next morning, I woke up to three sailboats rowing by. The sailors had a tough year.

Monday evening, just before sunset, first Windturn and then Calypso and One-Eyed Jake passed by in Floozie as they began their Charlotte Harbor crossing. I paddled out to cheer them on, and Mary and I raced with our SUP paddles. I jokingly said I wished I could cross with them on that windless evening. Part way through their crossing, the wind came way up. Such is the fickle March weather of Watertribe.

Kevin and I paddled and sailed around the north end of Charlotte Harbor for several days. On our last night, we rode out our first squall on the boat. Our jib came undone, and we fought to retie it. But we were safe in a protected anchorage, and we thought of those in the direct path of the storm. A reality check—Anything can happen in the course of the race. Completing the Ultramarathon gave me confidence but also showed where I can improve for next year’s Everglades Challenge. Let the training begin.

Fair winds and farewell until hext year. See you on the beach in 2025!

Winds, Waves, and Wake in the Ten Thousand Islands

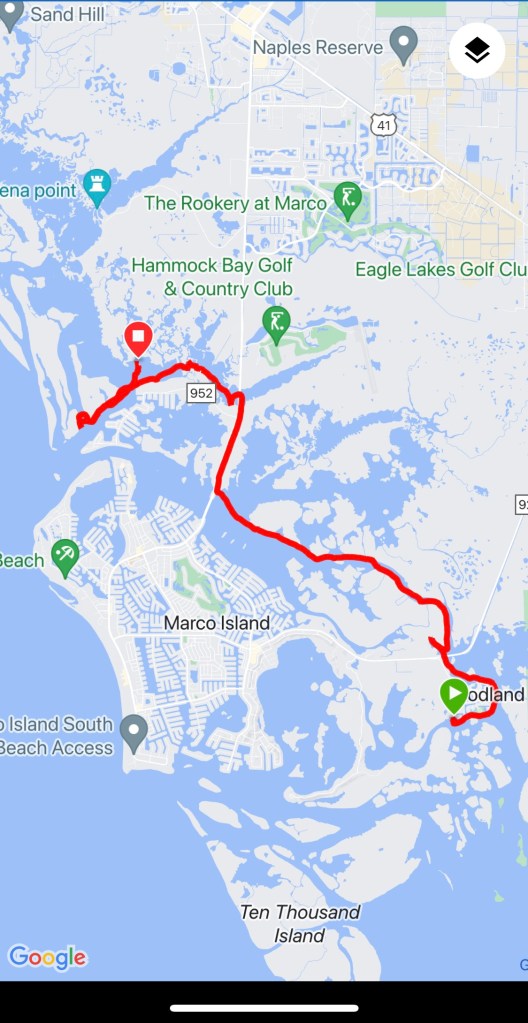

A break in the wearther between storms — we’re off! With board, board, and gear, Kevin and I fought wind and rain to reach Goodland, Florida. Our plan: 5 days exploring land and water in Rookery Bay and the Ten Thousand Islands to test new gear. My new board — a Sic Maui RS Atlantis 14′ x 24″ — and new rigging for our floating tent, a Sanibel 18 sailboat. New gear almost always creates an adventure..

First up: launching in the midst of a marina make-over. Jackhammers pounded our ears as we set up the boat. By late Thursday afternoon, we were anchored near the marina and ready to north towards the Isle of Capri the next morning.

Friday’s goal: a Johnson Bay anchorage. Kevin sailed out Caxambas Pass, along the outside, and back up Big Marco Pass. I paddled up the Marco River past Goodland, though the mangroves near Paddlers Park, and into Johnson Bay. I sat on the beach at the mouth of the pass, watching for Kevin and enjoying the clear water and white sand. I knew the boat wake and shoals would make for a challenging sail up the pass. The tides didn’t favor either of us that day, but we still made it to our anchorage on time.

Saturday: exploring nearby bays and the islands near Big Marco Pass. Wind and waves helped us test our gear. Kevin tweaked new reefing and rigging systems, and I worked with wind and boat wake in the mangrove channels. Boat wake in narrow channels is challenging because you get both the original swell and refracting waves. The Atlantis board is a dug-out style, meaning that its higher walls give both secondary stability and keep me closer to the water. Even though this new board is narrower than my other board, it handles conditions well.

A sporty day en route to Caxambas Pass! The wind dropped, but the waves continued rolling in. We rode the tide out Big Marco Pass, and a welcome tailwind pushed us along the coast of Marco Island towards Caxambas Pass. I had to stay outside the breaking waves or risk getting barrel-rolled in the surf. Not fun with a loaded board. Kevin sailed around the outside, while I explored bays and islands around Caxambas Pass and Dickman Point.

We anchored in Caxambas Pass that night. hoping for protection from a north wind. The wind never rose as expected, but the strength of the current in Caxambas Pass surprised us. Tying off the board to the boat was difficult as I held a rope in one hand while tying off with the other. Failure was not an option.

Sunday — a glorious day for me with clear skies and no wind. For sailors, not so much. I saw birds along the Morgan River, relaxed on Cape Romano, and watched sea life below as I crossed the sand flats in Gullivan Bay. Meanwhile, Kevin dozed while KneeDeep heaved to and drifted slowly.

We met later that afternoon near Tripod Key, a short distance from our take-out in Goodland. Even then, as predicted, the weather was changing, and we wanted an easy exit. As I was paddling up Coon Key Pass, I chatted briefly with a paddler headed out for the night. It turned out to be Kayak Flexafari, a paddler whom I followed but had not yet met in person. Small world and great to meet in person.

As predicted, the wind came up the next morning. Fun enough for a sporty sail and paddle in the morning, but seriously gusty by the afternoon. Taking out the sailboat was the biggest challenge of the trip. Overall, we lucked out with our weather window. Enough conditions to make things interesting, but no white knuckles. And we almost followed our Plan A. Usually we’re down to Plan G by the time the trip is over.

The Ten Thousand Islands, Rookery Bay, and Everglades region is one of my favorite places in Florida. White sand beaches and spectacular sea and bird life. With all the islands, rivers, and channels, I always find something new to explore. On this SUP and sail trip, Kevin and I had the luxury of our floating tent. But Rookery Bay and the Ten Thousand Islands offers plenty of white sand beach camping opportunities, sites I have used on previous trips. I’m looking forward to our next trip back in January.

Racing around Key West on a Paddleboard

Key West Paddle Classic 2023. A 12 mile circumnavigation of Key West on the paddle craft of your choice. Wind, waves, and tide. Clockwise around Key West–this course has something for everyone. As their pages promises “more FUN than most people have in a year.”

By 7 :30am, Kevin and I joined the stream of paddlers picking up race packets, unloading gear, and seeking coffee. At our 8:30am safety meeting, the race director noted that the predicted 8-9 mph winds were instead 13 mph and that storms might reach Key West mid-race. Paddleboards and prone boards would start at 9 am, and kayaks, OC 1 and 2s, and the dragonboats at 9:30.

The guide boat led us out to the start, then 30 seconds,and go! The first leg: south towards the southernmost point of the continental US and west towards Fort Zachary Taylor State Park. Just stay upright, I thought. The southeast winds offered some push, but the swell and rollers kept my focus on balance. I braved a few strokes on my left, but continual right side paddling kept me upright—mostly. Playing in swell and surf this summer paid off here. But, I wondered, do I really want to move to a narrower board this year?

Around the corner–relief! The swell eased beyond Fort Zachary Taylor State Park, and we traded our tailwind for an incoming tide passing through Key West Harbor and the Coast Guard station. I moved into the tidal waters ripping under the Fleming Key Bridge, and my speed rocketed to over 6 mph. Thank you tide. That was the easy part. I knew I would pay dearly going back out Cow Key Channel.

Fair winds and clear skies through the sailboat mooring field and northeast along Dredger Key. Almost like vacation paddling. Well, except that the black cloud in the distance now loomed straight ahead. Motivation—I did not want to be on the open water between Dredger Key and Cow Key Channel if a storm blew up.

The OC1 and 2s, kayaks, and dragonboats had caught up to us, and all of us fought the headwind and, now, incoming tide. The mangroves that lined Cow Key Channel grew larger, and finally I was across. My speed plummeted as I fought the incoming tide under the bridge. No surprise, I had seen the tide ripping through the day before and wondered if I could even paddle against it. But I made it under the bridge and headed towards the open water that would bring me to the finish line.

But not yet. The squall finally hit. Wind and rain, but fortunately no thunder and lightning. It passed quickly, and the winds dropped. I followed the sea wall towards the open water and then perhaps the longest 2-ish miles ever. Was that the most fun part?

Back in the chop and again paddling for balance more than speed. Nobody was around me, and the paddlers I thought I was following turned out to be navigational markers. I passed the airport and the Margaritaville Resort, too tired (or seasick) to even sing Jimmy Buffett songs. Towards the end, my stroke devolved to a death-zombie pace, and I fell in several times. I hoped to pick up my pace for that photo finish but settled for not throwing up and not crashing into the finish line. (Note to self: pack dramamine in my first aid kit.)

3 hours, 10 minutes, I finished! Kevin was waiting at the finish. 2nd place Women’s SUP, and 12/30 overall SUP. Times ranged from 2 hours 10 minutes to about 4 hours 15 minutes. Revived by cold water and Dr. Pepper, we watched tired but happy paddlers complete the race.

The Key West Paddle Classic brings it on. Fun but challenging, and I’m sure it is different every year. The Lazy Dog crew ran a wonderful event with plenty of safety,on and off the water. The event raises funds for the Special Olympics, and they served cupcake sushi at lunch! I focused on this event over the summer, and it’s been the perfect kick-off for my Everglades Challenge training.

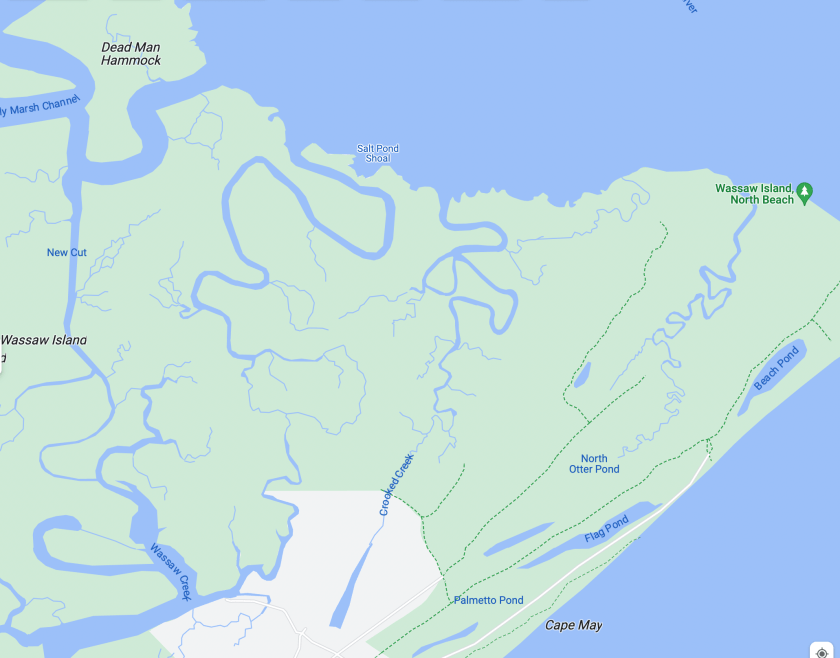

A Rare Summer Day on Wassaw Island

Low wind, ideal tides, and clear skies bode well for a day on Wassaw Island. Lured by the siren call of a deserted beach, we launched boat and board from the Landings Marina on Skidaway Island and rode the tide towards the north end of Wassaw Island.

Wassaw Island is one of the Sea Islands, a string of barrier islands that stretch from the Carolinas to north Florida. These islands saw waves of settlements, from indigenous peoples to enslaved African-Americans to 19th and 20th century conservationists hoping to preserve the ecological character of these islands. In particular, isolation on these islands fostered the preservation of African languages, foods, and traditions among the Gullah-Geechee people who had once comprised the bulk of the Sea Island residents.

Wassaw Island is one of several largely undeveloped islands along the Georgia coast, and we can thank wealthy industrialists and financiers for their semi-wild condition. Shortly after the Civil War, the Parson family from Maine bought the Wassaw and later transferred ownership to the US government to prevent development, forming the Wassaw National Wildlife Refuge. Today, Wassaw and nearby Little Tybee, Ossabaw and St. Catherine’s provide critical habitat for this marine ecosystem, and the isolated beaches foster an almost unimaginable sense of solitude and wilderness.

These islands are accessible only by boat, a perfect day trip for paddlers. However, this is coastal paddling, so it is important to wait for the right wind and tide conditions. Coastal Georgia boasts tides of up to 8-10′ feet, so that is alot of water moving in and out of these rivers and sounds.

From the Landings Marina, we paddled approximately 6 miles down the Wilmington River, across Romerly Marsh Creek, and landed on the north end. We carried our gear above the high tide line, hoping the trees might offer even the tiniest bit of shade. Then, a long refreshing float and our first wildlife encounter. A large stingray reminded us do the stingray shuffle.

Cooled off by our float and Kathryn’s watermelon, we walked toward a laerge stone block just offshore. This, Kathryn said, is what remains of Battery Morgan, a gun battery constructed during the Spanish-American War. That this block was once well onshore reveals just how much the sand and islands change over the years.

The block marked the entrance to the island’s dirt roads and a self-guided cell phone tour. We ambled slowly up the road, then quickly marched back out when the mosquito brigade emerged in force. The pond and the birds could wait until the colder months.

After fleeing the mosquitos and any other critters inhabiting the interior, we wandered through the dead trees on the point. Storms and shifting tides create haunting boneyards of dead trees that appear on all of these barrier islands. These trees also function as a reef of sorts, providing shelter for fish and incubating oysters.

These barrier islands and the marshes surrounding them host great biodiversity, both on land and sea. The dark waters of estuaries—where the waters of rivers and the sea mingle—reveal life, or organic matter, and it is a mistake to dismiss this water as simply “dirty”, as some do. The biologically rich waters of marshes and estuaries support juvenile fish, that often need a mix of fresh and salt water, and the microorganisms that feed them.

As we paddled, I saw several turtle heads popping up and back down as soon as they saw us. The turtle population along the Georgia coast has risen, thanks to the efforts of volunteers on the different islands. Over the season, volunteers mark nests, protect the nests, and protect hatchlings as they make their way to the sea. The Caretta Project allows volunteers to stay on Wassaw Island for a week to identify nests and/or protect hatchlings, depending on the time. We saw several of signs which, we assume, mark regions for the turtle volunteers. An amazing week, for sure.

Walking back to our gear, we noticed a horseshoe crab trapped in the sand. As we removed sand to free it, its tail twitched, and finally it swam away. Although horseshoe crabs might seem ubiquitous on the Gulf and Atlantic coast, their numbered have dwindled, due to both environmental factors and their blood being used for biomedical reasons.

And time for us to leave as well—an incoming tide, and the wind at our backs. Instead of retracing our steps, we detoured past the oyster mound at Dead Man’s Hammock, wound our way through Old Romerly Marsh Channel, and then back across Romerly Marsh Creek to the Wilmington River. Kathryn warned, me not to take that tempting left up Romerly Marsh Creek. It’s a mistake you do not repeat.

We could have detoured more, but thoughts of of Leopold’s ice cream, a Savannah delicacy that my grandmother remembered from her childhood, fueled a speedy return. We slowed briefly to watch several baby sharks playing and feeding, then went to feed ourselves. Sitting on the marina deck, we reflected on such an unusual summer day—no signs of the afternoon storms. Typically signs of building storms chase us off the water by early afternoon. So while we lucked out on the day’s conditions, in reality we are even luckier to have such a biologically and culturally significant area to explore.

Whales Every Day: Paddling Alaska’s Marine Highway

Early one morning in June 2019, I paddled my 16’ Pilgrim Expedition kayak through Skagway Harbor Marina, past rows of sailboats, fishing boats, and charters and finally beyond the cruise ships towards Lynn Canal. Skagway Harbor is the northern terminus of the Inside Passage, and our foursome—Dawn, David, Anthony, and myself—were beginning our 550 mile journey south to Prince Rupert, BC. We had risen at 4 am to beat the predicted afternoon winds, a routine we maintained for the entire journey. After months of packing, planning, and charting, we were finally on the road, southbound down the Alaska Marine Highway.

A Norwegian cruise ship had just arrived, and soon passengers would flood Skagway, buying t-shirts, jewelry, and raincoats. The previous night I watched a Disney cruise ship leave Skagway’s small harbor, tooting a familiar Disney melody to signal its departure. We passed the ferry terminal where the Alaska Ferry ‘Malaspina’ had carried us along with our boats and piles of gear. The thirty-eight hour ride—what some call the poor man’s cruise—previewed what we would see over the next month. For others, though, ferries are a lifeline and primary means of transportation. And here lies the reality and, perhaps, the beauty of the Inside Passage—cruise ships, ferries, and fishing boats also ply this swath of Alaskan wilderness.

“Whales every day,” Dawn had promised. True, few days passed without whale spouts or, even better, the fluke indicating the whale’s deep dive. Six weeks in Alaskan wilderness lured me, but so did the people and towns that populated Alaska’s Marine Highway, a segment of the Inside Passage. The Inside Passage is an approximately 1,000 mile route from Seattle, WA to Skagway, AK so named because the barrier islands buffer ocean swells from the Gulf of Alaska. The Inside Passage links people and places along southeast Alaska’s roadless coastal region, just as rivers served as highways throughout the lower 48 prior to roads. I embarked on this journey seeking adventure, but, in the end, my trip resembled a great American road trip, a mixture of crowds and solitude, rambling conversations and introspection.

Skagway’s crowded marina faded behind us, and the rocky shores of the mile-wide Lynn Canal surrounded us. Clear skies and glassy seas made our first day 15 mile paddle to Haines, Alaska a perfect shake-out day. For the first hour, the bear barrel in my cockpit cramped my legs, and I was grateful for our calm conditions. I had practiced cramming weeks of food, water, and gear into my boat again and again, but it still didn’t fit. At our first stop, I rearranged the barrel and other gear, a big improvement. Midway through the trip, I mailed home the bear barrel and other seemingly useless things—how could I still have too much stuff in the confines of a kayak?

A headwind made our last few miles into Haines difficult, no sooner than we paddled into the harbor the wind laid down. We pulled our boats onto the boat ramp and looked up towards the town. Southeast Alaska’s 12-18’ tidal range means that boat ramps are quite steep at low tide. The Harbormaster directed us to the nearby campground and pointed our carts to ferry our gear up the hill. No sooner than I had loaded a cart, a man called out “I’ve got a truck” and hauled our boats and gear to the campground. We wouldn’t have this luxury in our wilderness sites, but his kindness and a coin-operated shower crowned our first day. Harbormasters, shopkeepers, and random strangers—Alaskan hospitality is unparalleled. The harsh environment fosters both independence and interdependence because survival depends on relying on each other, a lesson paddlers learn well.

Skagway to Juneau: Headwinds on the Lynn Canal

By 6 am the following morning, we had packed, carried gear and kayaks down the ramp, and begun paddling south towards Juneau. Charts covered the decks of our kayaks, but navigating Skagway to Juneau is straightforward—follow the Lynn Canal south. The Lynn Canal is actually an inlet and considered the ‘Gateway to the Yukon.’ Over a hundred years ago, more than 100,000 prospectors traveled north up the Lynn Canal to stake a claim on the Klondike Gold fields. Many died, but many remained, transforming life in southeast Alaska forever. The Gold Rush began a population influx of North Americans and Russians into native populations, creating traumas and tensions that continue today.

We weren’t alone in the canal—cruise ships, fishing boats, and ferries motored past us. Cruise ships mostly passed in the late evening or early morning, often when we were getting ready for bed or packing up. I watched the boats as they passed, wondering what people were doing or if they even knew we were there. The ships seemed close but their wakes didn’t reach us until long after they passed. So many people in the canal, but we were so very alone.

The wind can be your friend or enemy in a canal. While preparing for the trip, we learned that the Inside Passage doesn’t have either northerly or southerly prevailing winds, so a fifty percent chance of headwinds on any given day. But, headwind or tailwind, a canal funnels wind. Leaving Haines, the winds increased to over 20 knots in our faces, and we crossed the mile-wide channel, hoping the canal might offer a windbreak. Headwinds and breaking waves made the crossing feel like paddling on a treadmill. The scenery never changed. We kept going—what choice did we have, and finally reached a beach on the tidal flats where glacial Katzehin River joins the Lynn Canal.

Our team had trained extensively in rough water, in coastal regions of the UK and the US, and the conditions were well within our skill sets. But Alaska’s remoteness and cold temperatures figure large in assessing risk so we decided to camp for the night. A rescue in these cold conditions would be dangerous. The cold water chilled us, even with our drysuits, and fleece layers, and my hands had become stiff with cold, even with paddling mitts. We got out of our boats to search for one of those campsites that had looked so inviting from afar. We sloshed upstream through ribbons of water snaking across the tidal flat, towing our boats with our safety lines. Finally, we reached a high point, above the presumed high tide line, and found a home for the night. Warm and dry, I didn’t let myself think about the bear tracks running through our site.

Every night, after dinner, I sat in my tent and listened to the weather report on my VHF radio. We were beyond cell phone reception. Knowing the wind direction and speed helped us plan the next day’s paddle. Most days we paddled between 20 and 25 miles, stopping for lunch and an occasional break. Paddling point to point rather than along shore cut our distance but made landings and breaks more difficult. Sometimes, I was so stiff by the time we stopped, I fell out of the boat into the water. I have never loved my drysuit more.

Several days beyond Haines and only a short distance from Juneau, our radios alerted us to a storm blowing up the canal, a storm fierce enough to warrant a weather day. We aimed for Bridget Cove, hoping to find refuge from the oncoming storm. Only a short distance by road from Juneau, Bridget Cove is a popular getaway spot. Another example of Alaskan hospitality, a man let us stay in Camp Freedom, a campsite and fire put area his son had built, and we rode out the storm in relative luxury. Only several days into the trip, I was starting to realize that people might be the highlight of our wilderness adventure. Looking back so many road trips and adventures, I remember the people I’ve met along the way.

Almost to Juneau, but first the Mendenhall flats, a mudscape impassable in anything other than high tide. Fortunately, Juneau’s tide peaked at noon so we reached the flats around 9:30 am to ride the tide to hot food and clean sheets. We paddled to the edge of the flats where the water diminished to a trickle. The navigational markers told us where the tide would flood, so we waited. And waited. Inch by inch, we muscled our boats down the slowly rising stream. High above us, small planes buzzed, carrying tourists to see Mendenhall Glacier, a sight we never saw. I knew Juneau was near, and my patience was wearing thin. The water rose enough to carry us, just barely, and our boats lurched forwards and backwards. We bumped the river’s edge and each other, as if the Three Stooges had possessed our boats. Bumper boats and warm showers in our near future, we laughed and laughed.

Juneau to Petersburg: Whales Tails, Bergie Bits and a Holey Boat

Clean sheets, a hot meal, and dry gear—I felt like a princess and a regular tourist. I bought stuff and shipped it home, toured museums, and drank too much wine. I walked the streets, upstream and down through throngs of disembarking cruise ship passengers. Surely some of these people had floated by our campsites, but miles of water and tons of steel no longer separated us. Now all of us crowded the streets, evaluating which attractions or stores merited a visit during our short time ashore.

Thirty-six hours later, we were ready to get back on the water and back to solitude. On a rainy Sunday morning, we perched on the floating docks at the Aurora Harbor Basin and crammed our gear, food, and water back into our boats. Even though we repacked daily, somehow the gear never fit the same way twice. My cockpit seemed suspiciously full of water, and after removing some gear, a small geyser erupted below my footpegs. My boat needed repair and fast. Everyone weighed in—the harbormaster, local sailors, and my team, until the marina hive mind arrived at a consensus: Flextape. I was skeptical. Petersburg, our next stop, lay over a hundred miles south. For the first several hours, I checked the repair obsessively, releasing my skirt to check for water. Only fiberglass and a strip of Flextape separated me from Alaskan waters. I continued checking over the next several days, but less frequently as I began to trust that my repair would hold. And it held until we reached Petersburg, where my boat received a proper repair.

We left Juneau and its crowded streets and joined the stream of marine traffic in Juneau’s harbor. We crossed the Gastineau Channel to avoid congestion, but a constant buzz alerted us to landing seaplanes. I’m used to looking left and right when crossing boat channels, but rarely up. I got used to it quickly—one more oddity that became the norm. Alaska’s coastline and roadless areas make seaplanes a vital part of transportation, and they, too, follow this marine highway.

We continued south down the Lynn Canal, past Point Arden to the west and Bishop Point on right, and on past Slocum Inlet, Taku Harbor, Limestone Inlet, and Point Anmer. Each name represented a crossing, a point of interest, or a campsite. Months before, charts spread across my living room, I studied these sites and considered angles for crossing large and possibly treacherous inlets. Abstracted from the realities of wind, waves, and weather, these sites seemed mysterious, but they became embodied as the daily conditions dictated our paddling and camping.

The Juneau-Petersburg was the coldest and rainiest of the trip. Several nights during this leg, I woke up hungry in the middle of the night, but the thought of grizzlies killed any hope of a midnight snack. Day after day, we set up camp in the rain and broke camp in the rain. Nothing escaped the moisture. But one glorious evening, though, the sun emerged and stayed out just long enough to dry out gear and shake off the black sand from the previous night’s campsite. Dry clothes, dry bag, and dry tent—pure joy and a precious luxury! And even more fun, a young couple within weeks of completing the Inside Passage south to north joined us on our gravel beach. We traded stories and tips about upcoming highlights of our trips. The only fellow paddlers we met during our entire trip.

We continued south down the Lynn Canal, past Point Arden to the west and Bishop Point on right, and on past Slocum Inlet, Taku Harbor, Limestone Inlet, and Point Anmer. Each name represented a crossing, a point of interest, or a campsite. Months before, charts spread across my living room, I studied these sites and considered angles for crossing large and possibly treacherous inlets. Abstracted from the realities of wind, waves, and weather, these sites seemed mysterious, but they became embodied as the daily conditions dictated our paddling and camping.

The Juneau-Petersburg was the coldest and rainiest of the trip. Several nights during this leg, I woke up hungry in the middle of the night, but the thought of grizzlies killed any hope of a midnight snack. Day after day, we set up camp in the rain and broke camp in the rain. Nothing escaped the moisture. But one glorious evening, though, the sun emerged and stayed out just long enough to dry out gear and shake off the black sand from the previous night’s campsite. Dry clothes, dry bag, and dry tent—pure joy and a precious luxury! And even more fun, a young couple within weeks of completing the Inside Passage south to north joined us on our gravel beach. We traded stories and tips about upcoming highlights of our trips. The only fellow paddlers we met during our entire trip.

This rainy period also offered one of our trip’s greatest challenges—a foggy crossing of Tracy Arm in Stephens Passage. Denis Dwyer who has written extensively on the Inside Passage designates crossing Tracy Arm as a ‘crux move’ on the Inside Passage because cruise ships and tours enter this fjord to see whales and glaciers. Under any circumstance, crossings warrant caution: in addition to boat traffic, winds, tides, and currents create swell and potentially hazardous conditions. Fog adds another element of danger and beauty as well. Like most paddlers, we anticipated crossing in the mornings when winds tend to be low. Surprisingly, afternoons rains made the sea glassy, and we mostly crossed inlets and bays in the late afternoon. We deliberated briefly at Tracy Arm: go or no go. The fog was light enough to see any approaching ships, so we settled on our angle, checked compasses, and began paddling. We didn’t linger or chat during the crossing, but kept an eye out for ships and fog. Once across, we were relieved and without incident happy that we had completed one of our trip’s crux moves.

While we paddled down Stephens Passage past Tracy Arm, icebergs, or bergie bits, as many call them, took shape through the fog. The grey skies and fog made their eerie blue light even more dramatic. For the next several days, we tracked bergie bits as they moved miles and miles with the daily tidal flows. The bergie bits, along with the cruise ships, put the vastness of Alaska’s waterways in perspective: after paddling all day towards a ‘tiny’ bergie bit, I reached an ice mass that was indeed larger than my house.

Despite the cold and rain, this leg had few windy days which meant that we had plenty of time for sightseeing and thinking. Sometimes I chatted with Dawn, and we guessed cloud shapes. But mostly, we paddled on, lost in our own thoughts, and my mind wandered. I thought about my life in Florida, and what I wanted to do when I got back. Before the internet, before gadgets, I rode buses, trains, and planes, staring out the window, sometimes bored, sometimes thinking. This time helped me sort things out, and I returned home refreshed and with answers or new approaches to big questions in my life. More often now I scroll through my iPhone, and I wonder if the freedom to space out is a luxury that we have lost. The freedom of not being tethered or entertained.

These glassy seas also gave us the most whale sightings, or soundings. The sound of their spouts carried for miles, and we heard them before we saw them. After several, usually three, spouts, they breached, and, if we were lucky, we saw the tail as they dove deep. Stellar sea lions, otters, and seals also popped up. Seals, with their dog-like heads, popped up to watch us. Stellar sea lions, known to be aggressive, swam up behind us, revealed first by their heavy breathing. Sea kayaks don’t turn very fast, and the sound of heavy breathing right behind me always made me paddle faster.

One of my greatest fears was a close encounter with a bear, but we saw relatively few bears. The salmon were running late that year so the bears remained high in the mountains, eating berries. My Alaskan friends take bears in stride, just as Floridians co-exist with alligators and snakes, but I was happy that they stayed far away.

Our glassy seas enabled us to complete this leg faster than we anticipated. Even though we had trained for—and hoped for—more exciting conditions, too little is better than too much. We had all heard stories of trips gone bad. We reached Petersburg on a Friday morning, again excited for showers, food, and clean clothes.

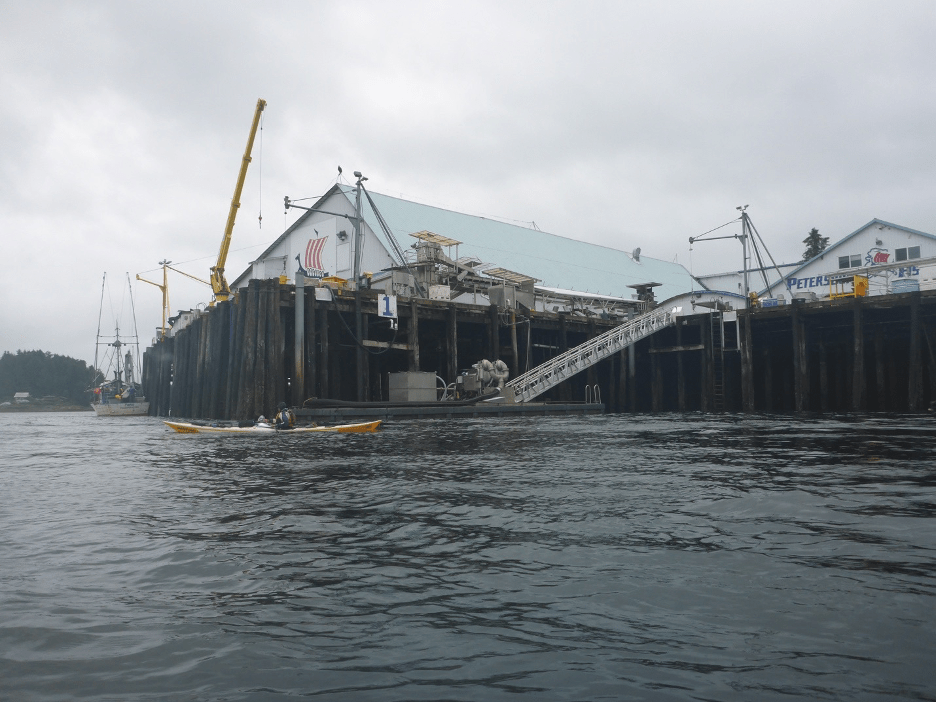

Petersburg to Ketchikan: Highs, Lows and Mud Flats

A buoy covered with sea lions greeted us as we entered the Wrangell Narrows leading to Petersburg. Within an hour of arriving at the Petersburg marina, we had stored our gear, found lodging, and ordered fish sandwiches at Coastal Cold Storage, conveniently delivered to the Harbor Bar next door. My Pilgrim Expedition had been whisked away on a storage truck and reappeared Sunday morning, repaired by local kayaker Ken Hamilton. Even though I had stopped obsessing over the Flextape repair, a permanent repair was a huge relief. Such was my introduction to Petersburg, Alaska which—hands down—was my favorite stop on the marine highway.

Fishing boats and processing plants dominated the harbor, not cruise ships. The stores catered to tourists but also local or seasonal residents who needed cold weather gear and other supplies. The streets and stores were calm enough that I had time to speak and joke with local residents. A friend’s daughter was moving temporarily to Petersburg, and that gave me an opening to ask about life there. I felt sure that she would enjoy her months living there.

Again, cleaning myself, my clothing, and my gear dominated my time our shore leave, but I found time to visit almost every store on Petersburg’s main road, several of which allude to the town’s Norwegian heritage. We had missed the town’s Little Norway Festival which marks the start of the fishing season. My sense of adventure didn’t include trying the ‘Mystery Shots’ masked in brown paper bags at the Harbor Bar. The bartender told me that they mix random samples for these shots. I commented that my days of garbage can punch are long behind me.

Sunday morning came quickly. We carted our gear back down to the back down the ramps to the floating docks. It was mid-tide so the ramps less steep. Nonetheless, I gripped the cart’s handle tightly, imagining the nightmare scenario of cart and gear flying down the ramp and into the water. Timing our actions to the tides was critical during the trip but especially so the next morning when we crossed Dry Straits, a large mudflat just north of Wrangell.

Early the next morning we paddled south and soon the outlines of the mudflats appeared. A 6:17 AM high tide meant we faced the flats during the ebb. We saw channels, and our charts showed channels, but even those began to run dry. One large channel remained, and if we didn’t reach that channel, we would be stuck on the flats for hours until the tide flooded back. The mud was firm, unlike much of Alaskan mud, so we pulled our kayaks across the mud toward the channel. Dragging a loaded kayak across mud is strenuous work—sometimes I walked pulling the tow rope over my shoulder, and other times I walked backwards. No-one complained—it was simply something we had to do, and a warm and sunny sky eased the pain. Wind and rain would have made a different story.

Timing tidal flows occupied a great deal of time and mental space. Alaska’s vast tidal ranges made choosing a campsite difficult and a chore that could take several hours. From the ferry going north, we spotted beautiful beaches, but later realized that many of these were submerged at high tide. Like Goldilocks, we needed the just right beach. Steep enough to remain above the tide line, and a bay deep enough to remain passable at low tide. Daily, we checked our tide charts and the kelp line that marked the previous tide.

After finding a site, we shuttled boats and gear to high ground, a task that could take over an hour, depending on the tide and the condition of the beach. A slippery rocky beach could produce a trip-ending ankle injury that might require an evacuation, so, in reality, the most dangerous part of the trip. Dawn had designed straps with handles so that the four of us could carry one boat at a time, standing upright rather than stooped over. We stepped carefully, aiming for the small bits of sand or dry rock that offered secure footing.

After Wrangell, we pointed south down Zimovia Strait into Ernest Sound and beyond the tiny community of Meyers Chuck into the vast Clarence Strait. Again, good weather allowed us to cover miles quickly, and soon we were two days out from Ketchikan. This leg proved to be the hottest, and each night, the sun beat down on us until it dipped below the horizon sometime after 10 PM. I lay in my tent sweating and finally understood the phrase ‘stewed in your own juices’.

Unable to sleep, I lay in my tent and reviewed charts, my GPS, and my Garmin Inreach, something I did most nights before bed. My Garmin Inreach was both a rescue lifeline and a means to send short, Twitter-length messages to my husband. Being outside of cell service and the internet was freeing, but I appreciated the contact with Kevin and the knowledge that my Inreach could summon help, in itself a freedom of sorts. My younger self backpacking in the 1970s might have scoffed at these gadgets, but my older self considers them a lifeline. I still have mixed feelings about being tethered, but overall the Inreach and the connections it offers me freedom to disappear into the wilderness yet remain connected to my husband.

We saw few cruise ships on this leg because we veered off the Alaska Marine Highway. I found that I missed the cruise ships and ferries which were conspicuous by their absence. That surprise me, but empty roads can be creepy when you expect to see people. Beyond Meyers Chuck, we merged back onto the Marine Highway and joined in the parade of boats and seaplanes coming and going from Ketchikan. Even though my daily experience of the Alaska Marine Highway was mostly wilderness, the boat traffic and the anonymous people on them played a big role in my experience. I enjoyed seeing those big boats every day and wondering about the people on them. Even if the connection with those passengers was remote and abstract, I savored the connection to other people.

Cruise ships and crowds would reappear in Ketchikan. On our last night before Ketchikan, we crossed the Behm Canal and camped on Pt. Higgins at the edge of the forest.

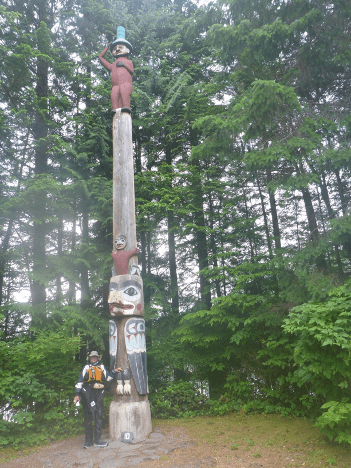

Ketchikan to Prince Rupert: Heading to Canada

Wind whistling through the trees woke me, and I knew immediately that our morning’s paddle down the Tsongas Narrows would be a slog. At some point overnight, grey skies obscured the previous evening’s warm sun, and I added an extra layer for warmth under my drysuit to prepare for the cold. Fighting the biggest headwind of the trip, we inched along, heads down, seeking windbreaks wherever possible.

A small beach out of the wind led us to Totem Bight State Historical Park, which housed replicas of totem poles from the region. Dawn and I walked through the park to see the totem poles, while cruise ship passengers stared at us in our drysuits and PFDs. There was some irony about emerging from the wilderness to a museum that showcased a culture deeply entwined with the natural world. The totem poles and accompanying signs educate people about the First Nations people who inhabited the region prior to European contact. The rangers I spoke with were proud of their efforts in restoring totem poles and educating visitors. But, outside of museums and stores that sold native art, I wondered how native culture meshed with the dominant north American ethos. I wondered what this exhibit meant to cruise ship passengers and others whose Alaska voyage was shaped by buffets, casinos, and shopping.

We heard Ketchikan before we saw it, and we dodged seaplanes and boats as we paddled to our harbor. Ketchikan stretches out along the eastern side of the Tsongas Narrows waterfront, and its airport sits across the water on the west. A small ferry carries passengers back and forth. Perhaps because I stayed in a hotel across from the cruise ships, Ketchikan seemed louder than anywhere else. But this vantage point demonstrated the small town rhythms of Ketchikan. During the day, cruise ship passengers dominate the town, but, after 7 PM, after passengers reboard their ships, the residents emerge from their homes and shops. The sounds of crowds and shopkeepers entreating people to enter had disappeared. It was quiet. Locals strolled along the waterfront, and fisherman, lined the town’s creek, hoping for salmon to begin their run. The owner of one of the ubiquitous jewelry shops showed me her collection of native art and talked of life in Ketchikan. I told her of my kayak trip, and the next morning she photographed our departure and emailed the picture to me.

Prince Rupert, BC was calling. Three weeks of paddling, and we were within a week of completing a trip years in the making. Several large crossings remained, including the final crux move: Dixon Entrance, a large body of water open to swell from the Gulf of Alaska. But, weeks of paddling and multiple crossings behind me, my confidence had soared. I recalled our first day, the bear barrel crammed between my legs. Not an auspicious start. The logistics of getting ourselves, boats, and gear still loomed ahead. Dawn and I bought one-way tickets to Prince Rupert, not knowing how long the trip would take. David and Anthony drove gear and boats to Prince Rupert, and the question of ferry space back to the US nagged at them.

We continued south, accompanied by ferries and cruise ships, and our remaining days dwindled to three or four. On a gloriously sunny day, we stopped at the early hour of 3 PM to camp on a beach. This early day gave me a chance to savor our final days of the Alaskan wilderness. We assessed our site and the tide chart—the tidal range was over sixteen feet. We were near the Canadian border, and Alaska is one hour behind British Columbia. That night, at 2 AM, as the four of us stood, watching the tide creep towards our tents, wondering which time zone the tide obeyed. Fortunately the tide receded, but no-one slept much that night.

Our weather radios predicted a weather change, and by the next morning, winds and seas had risen. Not exactly desirable conditions for Dixon Entrance. We slogged across Observatory Inlet, fighting wind, tide, and current, another treadmill paddle. Once again, the scenery remained the same for hours, but we had no choice. Inch by inch, foot by foot, we made progress until we completed the crossing. Our reward—a pod of orcas played against the cliffs ahead of us!

Our goal that morning was Port Simpson or Lax Kw’alaams, BC, a small native community that we hoped would have cell service. It was time to scout options for our return home. Canadian charts and maps, I had noticed, included more native names than Alaskan charts. Just south of Dixon Entrance, for example, lies Haida Gwaii, that many know as Queen Charlotte Island. On our ferry ride north, a Tlingit crew member told us that many sites are now known by their first, or native, names, an important aspect of retaining cultural heritage.

Like many small communities in coastal Alaska and British Columbia, Port Simpson or Lax Kw’alaams relies upon ferry service. According to Google Maps, travel between the two towns requires both road and ferry. Even smaller routes are critical “roads” in a marine-based transportation system that provides access to necessary goods as well as medical care. But, in our port stops, I’d seen signs protesting imminent cuts to the ferries, and our ferry had already eliminated the bar service. Since then, ferry service on the Alaska Marine Highway has been drastically reduced, affecting residents and adventurers alike.

Prince Rupert: The End of the Road

We landed at the Cow Bay Marina in Prince Rupert. After a celebratory ice cream bar at the gift shop, we focused on our chores—unloading our boats, Canadian customs, and cleaning up. I had wondered if we wouldn’t all give a big whoop when we finished. Looking back, perhaps smaller, and more significant, insights and burst of joy replaced that big whoop. Perhaps, this the end of this journey was too much to take in all at once. We had excitement for sure, whales, wind, and seals, and glimpsed life in the few exits along the Alaska Marine Highway. And this wilderness highway spared me billboards like the incessant “South of the Border” signs on I-95 that I loved as a child. But the time and space to think and dream that bored me as a child now felt like a paddling meditation. And this might have been the great gift I received: the time to simply be.

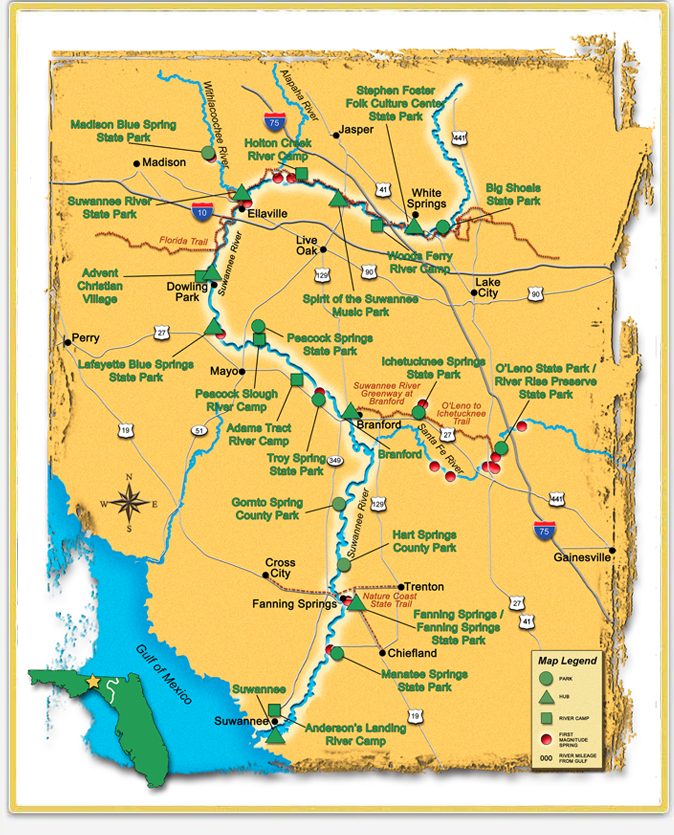

Shoals, Slow Flow, and a SUP on the Suwannee 230

7:30 am, Griffis Fish Camp, Fargo, Georgia. Paddlers in 18 watercraft—canoes, kayaks, and paddleboards—eager to start the Suwannee230. The Suwannee230 is a 230 miles race, from Griffis Fish Camp, just downstream of the Okefenokee Swamp, to Suwannee, Florida, where the Suwannee River meets the Gulf of Mexico.

The exposed sandy banks—flooded during last year’s race—hinted at the obstacles that we would paddle over, under, and around. In last year’s race, higher water obscured the river’s path, and several paddlers detoured into the maze of trees. This year, the lower water made the course clear but exposed obstacles we paddled over last year.

In the morning’s low light, we navigated the twists and turns of the Upper Suwannee, its character vastly different from the broad Lower Suwannee. I missed the boost I had enjoyed in earlier paddles. But no rain—even from Hurricane Ian—meant slow flows and a sporty collection of obstacles, shoals, rocks, and trees.

Soon, the entire group portaged portaged over a log that blocked the entire river, entertaining the campers drinking their morning coffee. On that first day, I paddled around blockages, slithered under trees, and tried to avoid catching my 3″ gummy fin on submerged branches.

Day 1 goal: to reach Big Shoals rapid, a mandatory portage, before dark. Yet, despite my obsessing over this portage the previous night, it was surprisingly easy in the dark. The sign, somewhat obscure in the daylight, reflected brightly under my headlamp’s glare. I hauled my board and gear, stuffed in a backpack, up the bank, along the short trail, and back down the rooty slope to the area beyond the rapid. I had packed minimally to reduce my time on the portage and was on my way by about midnight.

By this time, any ambient light had faded, and darkness shrouded the river. Columns of fog swirled around me, like dust devils, as if the river wasn’t already creepy enough. I paddled gingerly, knowing Little Shoals was less than a mile ahead. And, although I prefer letting my eyes adjust to the darkness, I turned on my headlamp and shined my bright dive flashlight around, even though I would hear the shoals before I saw them. Red eyes and yellow eyes all around—nothing creepy there. For the rest of the trip, the song “The Night Has a Thousand Eyes” ran through my head.

I thought I was prepared, headlamps, a dive flashlight, and my gummy, flexible fin. All of my rough water training stresses preparation, to avoid the “and there I was” situations. And yet there I was—running shoals in the dark on my 14′ SIC RS paddleboard which turned out to be remarkably sturdy. I lined my board over the first set as a tandem canoe with far superior lights flew by. Back on the board, I alternated paddling and shining my light as I navigated the remaining shoals.

Just before White Springs, a final shoal sheared off my fin, and I called it a night. I shone my light to find a campsite—the reason I carry that light, and found a sandbar to call home. I woke at 4:30 am to a pair of canoes—again, with better lights—navigating that shoal and went back to sleep for another hour.

Day 2. At the springhouse I retrieved the food and water I stashed. I had little sleep that night, and ambitious plans of a big mileage day faded throughout the day. I craved sleep, and I fantasized about sleep throughout the day. Spirit of the Suwannee Music Park, Suwannee River State Park, and finally the jarring lights of Advent Christian Village before I reached Dowling Park River Camp. And then I slept.

The next morning, Janice, director of Paddle Florida or perhaps an angel, brought me coffee and lasagna. To reduce gear, I didn’t bring a stove so hot coffee was heavenly.

Day 3—I needed big miles, at least 70. A cold front was coming, and I was about over the Suwannee—this year’s race was more demanding. But fortified by a good night’s sleep, coffee, and lasagna, I was ready to tackle the miles. Past Branford and Gornto Springs park, then darkness. As in the previous nights, I let my eyes adjust to the swath of light that revealed the river’s curves. And I read the water in this light for disturbances, branches for example, that could snag my fin. More than anything, I didn’t want to fall at night.

I briefly “rested” at the Hart Springs boat ramp, where camping is prohibited. My Spidey-sense woke me at 4:18, 12 minutes before my alarm. And 12 minutes before the police cruised by, where I stood, holding my paddle and not camping.

Day 4—a mere 35 miles to Bills Fish Camp. I launched into the darkness. My watch read only 2.1 mph. Stupid GPS watch. I stopped and restarted my course. Still slow. D’oh! I turned around and magically my speed doubled. All the other boat ramps had been on the left. Not that one.

At Fanning Springs, I stepped off the board and experienced a few seconds of “sea-legs.” Balancing in the dark—without visual markers—is harder than I thought! Several hours later, I surfed a downwind course as the cold front rolled in. So much fun, but I knew I would pay. I was so close to the finish when headwinds flipped my fun into a slog. Head down, I tucked into the vegetation and pushed through the final four miles.

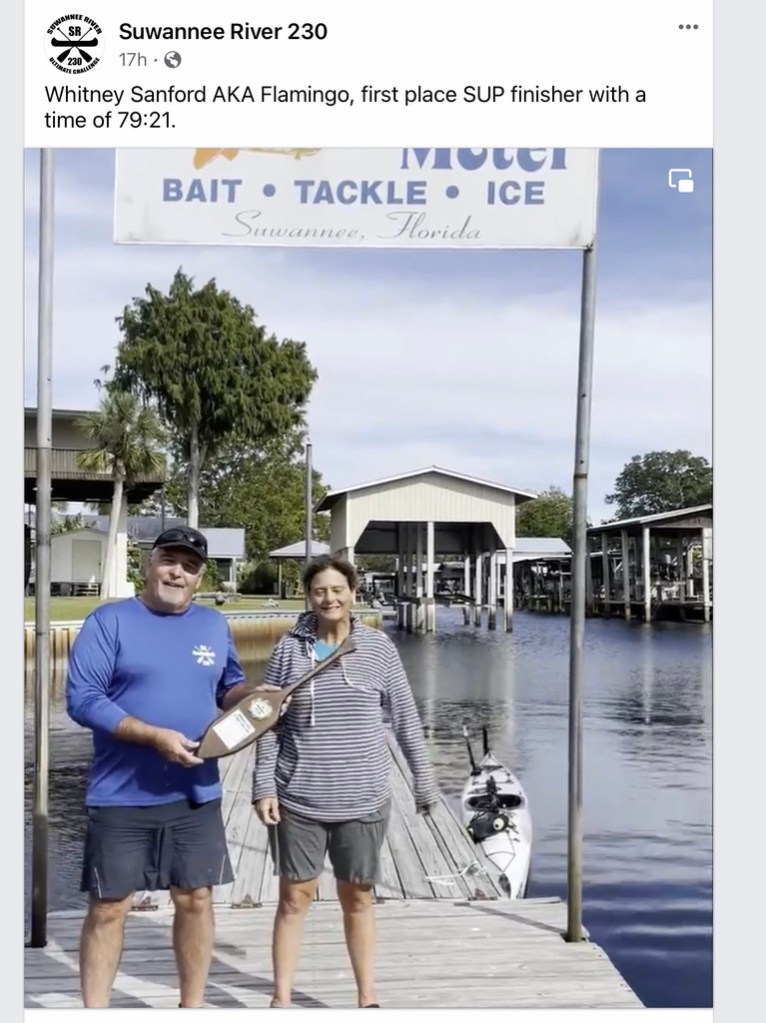

Done! Despite the low water and obstacles, I beat my previous time by over two hours. My training with Coach Larry Cain and Paddle Monster paid off! Still plenty of room for improvement, but the training and a reduced gear load really helped. Next up: Florida Circumnavigational Saltwater Paddling Trail (CT) and the Everglades Challenges. See you on the beach.

SUP and Sail Under the Sunshine Skyway

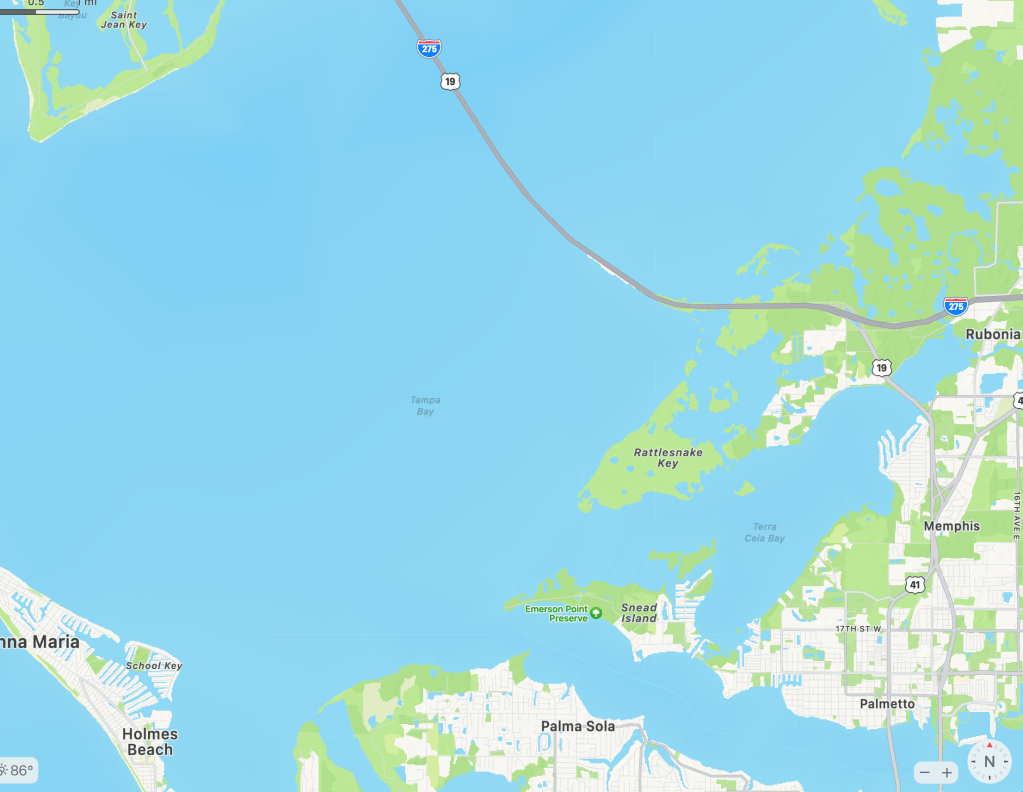

SUP and Sail in Tampa Bay in August? But why? The weather swings between dead calm and squalls, making both sailors and paddlers cranky. But we needed to test our Sanibel 18 sailboat—KneeDeep 1, newly rebuilt after two years languishing in the yard. So off we went, boat and board, to Terra Ceia, Florida at the south end of the Sunshine Skyway Bridge.

Our mission: prepare KneeDeep l to be our floating home for upcoming sailing and paddling trips. On our SUP and Sail trips, Kevin sails, I paddle my SUP, and we meet at a designated anchorage at the end of the day. A good test of our navigation skills as well as our relationship. With an 14″ draft, KneeDeep l is ideal for navigating the shoals of southwest Florida and the Everglades. But if our larger sailboat, an O’Day 222, is a floating tent with a vestibule, KneeDeep l is a floating bivy. A floating bivy that will shelter us for West Coast Trail Sailing Squadron trips and, more important, house Kevin during the Everglades Challenge in March while I’m paddling.

Terra Ceia and the south end of Tampa Bay was new to me, so I consulted Florida Paddling Trail Association‘s (FPTA) website which suggested several routes. Additionally, the Manatee County Paddling Guide offered routes as well as information about local history and the ecosystem. Brooke Longeval also shared a route around Rattlesnake Key and Emerson Point. In the end, I created my own routes, but these resources gave me a start.

Over the four days, I paddled to Emerson Point and around Rattlesnake Key, under the Sunshine Skyway Bridge, and partly across Tampa Bay towards the large American flag on Mullet Key, the start of the Everglades Challenge. The afternoon storms limited my range—I never wanted to be too far offshore when the inevitable storms blew up. And after a 52-mile training paddle the previous weekend, I needed to ease my way back into my Paddle Monster workouts. But I feel like I barely scratched the surface of the paddling this area offers.

In past years, Kevin and I have done multiday SUP and sail trips to southwest Florida, the Ten Thousand Islands, and the Everglades. Each trip has been a learning experience, both for Kevin on the boat and me on my board, and we debrief after each trip. What have we learned? What went wrong, or could have but fortunately didn’t? Our expedition sea kayak training has given us skills in open water, navigation, and marine communication as well as lessons in self-reliance. The latter is especially important because we are alone on our individual crafts, often miles apart. In particular, during the Everglades Challenge when I will be paddling and camping from my board, and Kevin will single-hand the sailboat.

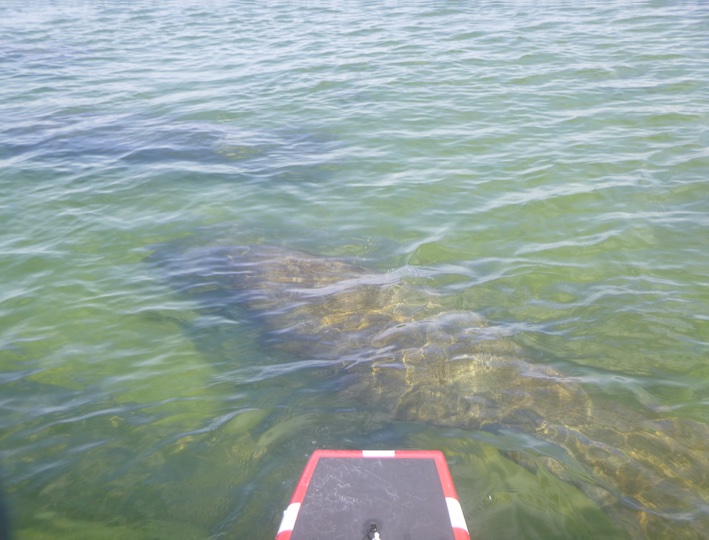

Terra Ceia is a small community in Manatee County surrounded by nature preserves, including the Terra Ceia Preserve State Park and the Terra Ceia Aquatic Preserve. Many of the areas I paddled were shallow grassy flats that provided habitat for juvenile fish, baby sharks, rays, and manatees. One day I ate lunch surrounded by a pod of manatees, and another morning I watched baby sharks stalk their breakfast, tiny fins thrashing left and right.

I hadn’t realized how significant this area was to Native American history. Terra Ceia and Emerson both house ceremonial mounds in which archaeologists have discovered multiple periods of Native American culture. The Madira Bickel Mound State Archaeological Site is accessible by both road and water, the backside anyway.

After paddling and sailing under the August sun, Kevin and I met most afternoons for a float.

Sailors and paddlers are never happy—either too much wind or too little. One afternoon, we floated and commented on the beautiful cloudscapes. But in the beauty lurks danger. I wondered if we weren’t tempting fate. Of course, we were.

The inevitable happened—a storm blew up over Bradenton, and Kevin rode it out on the boat while I, safe at the house, followed the storm’s progress on my phone. A stark reminder of how fast Florida’s weather can change.

Over adult beverages that evening, we pronounced our shake-out cruise a success. Kevin determined what KneeDeep l needed, and I explored the south end of Tampa Bay. Our next step: preparing KneeDeep l for multiday trips into the remote and shallow waters of the Everglades. We’ve done these trips on our larger boat, but how will this smaller boat fare in rough conditions? Let the training begin. March and the Everglades Challenge will be here before we know it!

A Early Start to Everglades Challenge 2023 Training

At 7 am, Chief gave the signal: the Everglades Challenge had begun. To my left and to my right, kayaks, sailboats, and one paddleboard launched into Tampa Bay, beginning the 300 mile journey to Key Largo. Despite my excitement and preparation, I stood on the beach, intimidated by the wind. The wind rose, and Chief offered me a Plan B start, meaning that I could start further south. I wasn’t sure how far I could go or even if I was still in the race, but after months of practice and training, I was grateful to be on the course.

I launched mid-afternoon onto Charlotte Harbor from Burnt Store Marina, a place I knew from a previous Sup and Sail trip with my husband Kevin. I hugged the shore as best I could, but any exposure gave me a taste of the larger conditions I had avoided.

I passed Matlacha at sunset and continued south as darkness fell, heading for Cape Coral and points beyond. Even though navigation was straightforward at this point, the darkness played tricks on me—at one point, I wondered if I was actually heading north. I never realized that Pine Island was so long!

Finally I reached the mouth of the Caloosahatchee River and a decision point. Given the easterly winds, I wasn’t sure I could hold my course, and the bay seemed like an awfully big place at night. What I knew rationally was the bridge to Sanibel seemed lit up like a casino, and the twinkling lights marking the different channels disoriented me (and confirmed that I need new glasses.) Even though I had only paddled 21 miles, I decided to make camp and navigate the crossing in the daytime.

As I lay awake at 3 am, listening to the tide lap inches from my bivy, I reflected on what went right and what went wrong. What went right? In the weeks before Watertribe, I winnowed my gear, lightening my load, and repacked it more efficiently, for example, my night paddling kit in a separate bag attached to my duffel. I had tested some of these systems on a trip to Panther Key where I met up with members of both Watertribe and West Coast Trailer Sailors and received some very welcome advice.

What went wrong, or better put, lessons learned? More wind practice. I felt strong enough to push on, but a windy crossing in the dark concerned me. I knew that this was the western end of the Okeechobee Waterway, where boats cross Florida from the Atlantic to the Gulf, and images of barges and freighters filled my head.

When I launched the next morning, small fishing boats rather than the massive cargo ships of my imagination dotted the becalmed seascape, and I crossed without incident to Bowditch Park in Fort Myers Beach.

My Sunday morning dreamscape shattered on the ICW in Fort Myers, which gave life to the term wind tunnel. I fought my way under the bridge and used the hulking steel boats as wind shelter. It pained me to pass Randy Wayne White’s Doc Ford Rum Bar and Grill, and but I knew that Doc Ford would just keep paddling. So I did.

In Estero Bay, a parade of pontoon and other boats streamed by, and I bobbed along in their wake. My board felt especially unstable, leading to several unplanned exits, and I didn’t confirm until that night that my fin had disappeared somewhere in Estero Bay. I sat down and paddled, and that led to another lesson learned: sitting works too. Once I was no longer a human sail, my speed increased, and paddling seated should help me handle bigger winds. But as my friend Kathryn helpfully noted, “Some people call that a kayak.” Point well taken.

Later I passed several fisherman who asked where I was going. I replied Wiggins Pass, the first thing that popped into my head. One said “That’s far, it’s windy” and asked if I needed a ride. No thanks, I’m good. And it was. One thing I love about the Everglades Challenge is the self-reliance it demands. I was alone, on a board, on a rocking and rolling Estero Bay. Whatever came up, I just needed to figure it out.

I continued towards Wiggins Pass, wending my way through a series of small channels. A tiki bar loaded with revelers motored by, and another sat anchored in the mangroves. If there ever were an epic illegal camping spot, that would be it. And I paddled on. I reached Wiggins Pass just as Flipper and Foco arrived, happy to share the spot with other tribers. Again, my skill rather than fitness prompted a stop. Once I left the pass, I would be in open water, and there were few, if any, camping options until Gordon Pass. Looking back, since the wind tended to drop at night, I would take advantage of that.

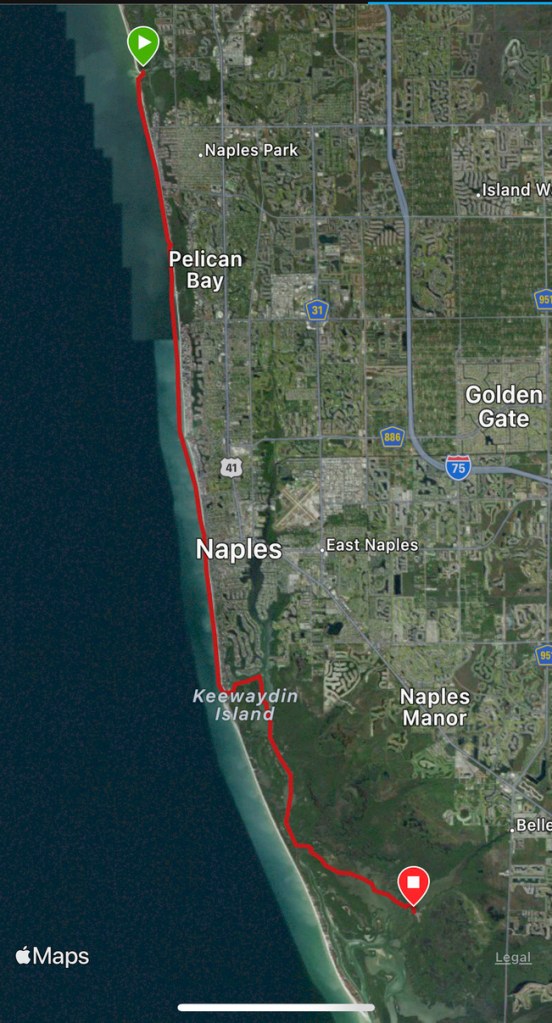

The next morning, I attached my spare fin and aimed for Naples. Rolling waves pushed me for the first several hours, until the winds rose up again. I entered Gordon Pass and fought my way through Dollar Bay towards Marco Island. There I made my final mistake.

At Panther Key, Andy said that if you have an out, you’ll take it. As I paddled towards the Marco Island, Kevin appeared in a kayak. It was just too easy. And that led to yet another lesson. I spent too much time on Windfinder, obsessing about predicted winds. My mistake: looking too far ahead. With some rest, I could have continued and taken advantage of diminished winds. Focus on the present.

2022 was my first attempt at the Everglades Challenge, or perhaps, a head start for Everglades Challenge 2023. (If only it counted for next years derby.) It was a terrific experience, and now I know better where to focus my training. In retrospect, I could have crossed Tampa Bay, and I have paddled successfully in bigger conditions, but I need to do it more of it. Even though some said we faced especially difficult headwinds this year, it seems like it just isn’t an Everglades Challenge without them—unless you’re going the wrong way. So, my prescription for myself: wind, waves, and open water crossings. And see you on the beach next March.