Visiting Anna Maria Island and Cortez, Florida reminded me just how much Florida’s histories, cultures, and ecologies are bound to the sea. Heavy winds and water torpedoed our original plan of sailing and anchoring near Tarpon springs. So, on Spring Break Eve, Kevin and I changed course to small boat sailing and onshore exploration of southwest Florida. The white sands and clear water of Anna Maria Island had enticed us for years, and the promise of renting sunfish and lasers at Bimini Bay Sailing sealed the deal. We loaded our car with gear to cover almost any imaginable water activity and headed to our last-minute booking at Silver Surf Resort in Bradenton Beach.

The next morning, we drove to Bimini Bay on the north end of Anna Maria Island where we met Brian and his fleet of small boats. Anna Maria Island is small-scale and relaxed, especially compared to neighboring Longboat Key. Bimini Bay Sailing, however, carried relaxed tropical paradise to a new level, and the ducks and cat that adopted Brian seemed to agree. We discovered a slice of heaven on this mangrove-ringed tip of land, and a small water-based business living light on the land and sea.

On our first day, the winds were too big for small boats. Our friends Jill and Scott joined us with their sailing kayak rigs, so we kayak-sailed and paddled boarded in the bay. The wind subsided on the following days, and we sailed the trimaran, sunfish, and lasers.

By midweek, the wind drove us onshore, and we headed to the fishing village of Cortez and Mote Aquarium. My research on the St Johns River taught me a great deal about people and their ties to their river economies and ecologies. Now I hoped to learn more about these relationships in a coastal environment.

“The grill opens at 11:30, but the bar’s open now.” The self-appointed welcoming committee cheerfully called out as Kevin and I walked into the Starfish Dockside Restaurant. The Starfish Company and Dockside Restaurant lies in the heart of Cortez, Florida, described as a “real Florida fishing village.” We heard about Cortez several years ago from a sailing friend and were curious to visit this piece of old Florida existing as a counterweight to Tampa’s urban sprawl. Cortez sits just across the bridge from Bradenton Beach on Anna Maria Island, but it felt another world and perhaps another era.

Despite its location in the middle of vacationland, Florida, Cortez remains a working fishing village and reminds visitors that many Floridians have—and still do—live intimately with the sea. A statue of a fisherman and a sign describing the history of Cortez mark the center of the two-block historic area.

In the post Civil War 1800s, commercial fisherman of English heritage relocated from the coastal Carolinas, drawn by the “wealth of fish, scallops, and other seafood.” They named the area the “Kitchen” and developed a a thriving fishing and processing industry, shipping fish to Tampa and Cedar key by rail. A sign outside the Starfish Company showcases the harvest from the sea.

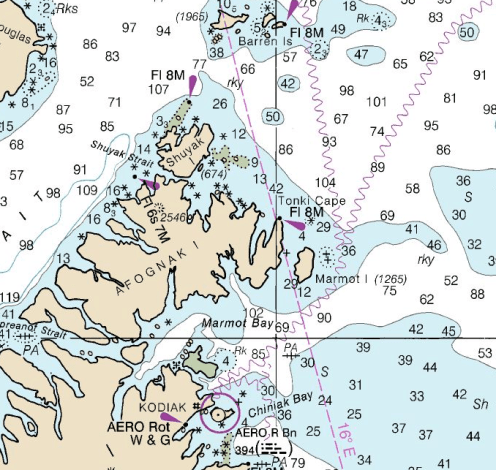

“The place names on the map are a symbol of the proud tradition of commercial fishing in Cortez. They constitute a form of local knowledge that is derived from years of fishing the inland waters. Some of the names have been passed from generation to generation. Although the origins of such names have faded from memory, their daily use by Cortezians reminds us of the fishing folklore heard time and again on the docks of Cortez.”

As we ate our grouper sandwiches, the fishing boats made clear that this was indeed a working harbor. The Starfish Company is fairly small, but the larger Bell Fish Company and Cortez Bait and Seafood are nearby.

That Cortez remains viable is a testament to their tenacity. Over twenty years ago, Florida instituted a gill net ban, which pitted commercial fishers against sportsmen, a move that devastated many small coastal fishing villages. Cortez adapted and survived, but I wonder how fishers and others will adapt to the growing threat of marine plastics.

After lunch, we visited the Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium on Longboat Key, one island south of Anna Maria Island. Driving past the sterile gated communities that lined Longboat Key heightened our appreciation for the friendliness and lack of pretention of Cortez and Anna Maria Island. Even so, our presence as tourists reminds me that our hotel and others have pushed fishers and other workers inland off the coast.

At Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium, Kevin and I joined the others who opted for an onshore day. We saw seahorses, sharks, otters, and turtles. But, most striking and stunning, we saw sculptures composed of marine plastics as part of the “Sea Debris: Awareness through Art.” When I walked inside the whale rib cage, I didn’t realize at first what I was seeing. Then, I realized what I was seeing: the ribs were constructed of detergent bottles.

I heard people muttering how sad it was, and I hope projects like this help us recognize the linkages between our use of plastics and the about the state of our oceans. Several years ago, I had my ‘year of plastics,’ where I learned about microplastics in the Caribbean seas and I hauled larger plastics off the Alaskan coastline.

Traveling around Florida constantly demonstrates me how our lives are intimately tied to our waters, rivers, and seas. Yet some now that warn that our “Coastal Environments are Collapsing“. Exhibits such as “Sea Debris” reminds me of their fragility, that so many lives and livelihoods, whether Brian’s sailboat rentals or a fishing village, depend on their health. What are we willing to do to insure the well-being of our waters and those that live in them and work on them?

This trip illustrated some realities of scientific data collection and helped me reflect on my own research methods, which have been primarily ethnographic. By training, I am an historian of religion, and I study both texts and people. I have done ethnographic research, for example, interviews and participation-observation in different communities. To collect data for my projects, I have

This trip illustrated some realities of scientific data collection and helped me reflect on my own research methods, which have been primarily ethnographic. By training, I am an historian of religion, and I study both texts and people. I have done ethnographic research, for example, interviews and participation-observation in different communities. To collect data for my projects, I have