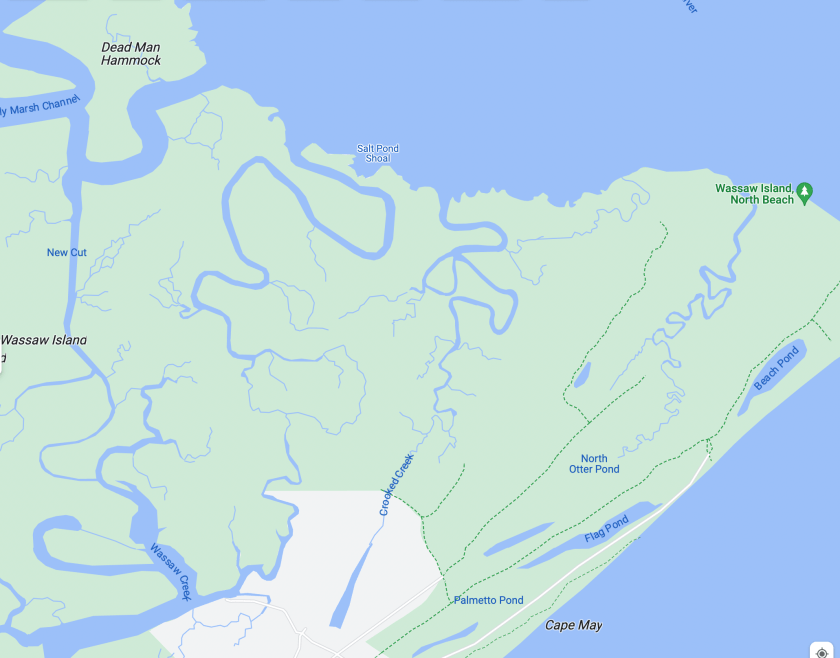

Low wind, ideal tides, and clear skies bode well for a day on Wassaw Island. Lured by the siren call of a deserted beach, we launched boat and board from the Landings Marina on Skidaway Island and rode the tide towards the north end of Wassaw Island.

Wassaw Island is one of the Sea Islands, a string of barrier islands that stretch from the Carolinas to north Florida. These islands saw waves of settlements, from indigenous peoples to enslaved African-Americans to 19th and 20th century conservationists hoping to preserve the ecological character of these islands. In particular, isolation on these islands fostered the preservation of African languages, foods, and traditions among the Gullah-Geechee people who had once comprised the bulk of the Sea Island residents.

Wassaw Island is one of several largely undeveloped islands along the Georgia coast, and we can thank wealthy industrialists and financiers for their semi-wild condition. Shortly after the Civil War, the Parson family from Maine bought the Wassaw and later transferred ownership to the US government to prevent development, forming the Wassaw National Wildlife Refuge. Today, Wassaw and nearby Little Tybee, Ossabaw and St. Catherine’s provide critical habitat for this marine ecosystem, and the isolated beaches foster an almost unimaginable sense of solitude and wilderness.

These islands are accessible only by boat, a perfect day trip for paddlers. However, this is coastal paddling, so it is important to wait for the right wind and tide conditions. Coastal Georgia boasts tides of up to 8-10′ feet, so that is alot of water moving in and out of these rivers and sounds.

From the Landings Marina, we paddled approximately 6 miles down the Wilmington River, across Romerly Marsh Creek, and landed on the north end. We carried our gear above the high tide line, hoping the trees might offer even the tiniest bit of shade. Then, a long refreshing float and our first wildlife encounter. A large stingray reminded us do the stingray shuffle.

Cooled off by our float and Kathryn’s watermelon, we walked toward a laerge stone block just offshore. This, Kathryn said, is what remains of Battery Morgan, a gun battery constructed during the Spanish-American War. That this block was once well onshore reveals just how much the sand and islands change over the years.

The block marked the entrance to the island’s dirt roads and a self-guided cell phone tour. We ambled slowly up the road, then quickly marched back out when the mosquito brigade emerged in force. The pond and the birds could wait until the colder months.

After fleeing the mosquitos and any other critters inhabiting the interior, we wandered through the dead trees on the point. Storms and shifting tides create haunting boneyards of dead trees that appear on all of these barrier islands. These trees also function as a reef of sorts, providing shelter for fish and incubating oysters.

These barrier islands and the marshes surrounding them host great biodiversity, both on land and sea. The dark waters of estuaries—where the waters of rivers and the sea mingle—reveal life, or organic matter, and it is a mistake to dismiss this water as simply “dirty”, as some do. The biologically rich waters of marshes and estuaries support juvenile fish, that often need a mix of fresh and salt water, and the microorganisms that feed them.

As we paddled, I saw several turtle heads popping up and back down as soon as they saw us. The turtle population along the Georgia coast has risen, thanks to the efforts of volunteers on the different islands. Over the season, volunteers mark nests, protect the nests, and protect hatchlings as they make their way to the sea. The Caretta Project allows volunteers to stay on Wassaw Island for a week to identify nests and/or protect hatchlings, depending on the time. We saw several of signs which, we assume, mark regions for the turtle volunteers. An amazing week, for sure.

Walking back to our gear, we noticed a horseshoe crab trapped in the sand. As we removed sand to free it, its tail twitched, and finally it swam away. Although horseshoe crabs might seem ubiquitous on the Gulf and Atlantic coast, their numbered have dwindled, due to both environmental factors and their blood being used for biomedical reasons.

And time for us to leave as well—an incoming tide, and the wind at our backs. Instead of retracing our steps, we detoured past the oyster mound at Dead Man’s Hammock, wound our way through Old Romerly Marsh Channel, and then back across Romerly Marsh Creek to the Wilmington River. Kathryn warned, me not to take that tempting left up Romerly Marsh Creek. It’s a mistake you do not repeat.

We could have detoured more, but thoughts of of Leopold’s ice cream, a Savannah delicacy that my grandmother remembered from her childhood, fueled a speedy return. We slowed briefly to watch several baby sharks playing and feeding, then went to feed ourselves. Sitting on the marina deck, we reflected on such an unusual summer day—no signs of the afternoon storms. Typically signs of building storms chase us off the water by early afternoon. So while we lucked out on the day’s conditions, in reality we are even luckier to have such a biologically and culturally significant area to explore.