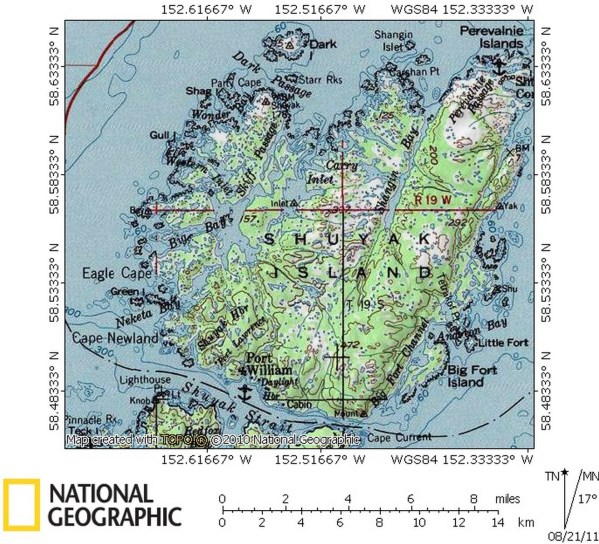

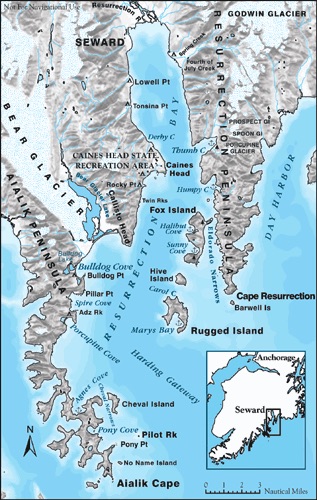

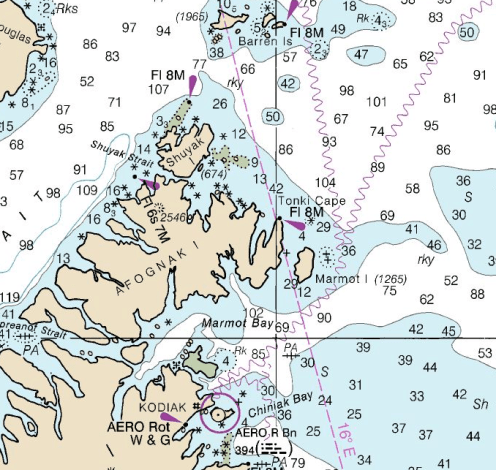

On Sunday, June 12, I awoke early, excited for my first ride on a float plane. We were headed for Shuyak Island State Park to collect marine debris using sea kayaks. Shuyak Island is the northernmost island in the Kodiak Archipelago, and the winds and currents of the Gulf of Alaska deposit tons of marine debris on its shores each year. Tom Pogson of the Island Trails Network received a grant from NOAA Marine Debris Program, and months ago, we had applied to participate in this great adventure—paddling in Alaska, float planes, abundant wildlife, and a chance to give back to a sport we love. How could any of us pass up this opportunity?

Our team of five had arrived in Kodiak several days early in case Kodiak’s notoriously changeable weather went bad. Dawn, Kevin, and I knew each other from previous kayak trips, and we met Fiona and Kate at Kodiak Island Brewery the night before. Fortunately. Sunday’s weather was clear and beautiful, and the pilot gave us a tour the land and water between Kodiak and Shuyak. Soon after we arrived, a mama brown bear and her two cubs sauntered down the beach and then up the hiking trail. After sorting out our tents, boats, and gear we paddled out around Eagle Point into the Gulf of Alaska, then surfed the swell home.

Over the next two weeks, we tackled Gulf-facing beaches as well as the protected shores inside Big Bay—the wind and swell determined our daily destinations. Big surf landings onto rocky shores would have been dangerous for both boats and bodies, and we knew that any rescue situation would be difficult and hazardous. An accident that might be a minor inconvenience in highly populated Florida could be life-threatening in remote Alaska.

We spent several days cleaning Dead Bird Beach, a two-mile stretch that faced southwest. In addition to a variety of small skeletons (hence the name), Dead Bird Beach was littered with plastics, ropes, and nets. The large plastic objects and buoys were easy to spot, while the nets and smaller plastics blended into the sand, rocks, and wood. Some objects were immediately identifiable—water bottles, fishing lures, and fly swatters. A Wal-Mart shipment of fly swatters and mini-basketballs marked with team logos had fallen off a cargo ship several years prior. Other materials less so, such as the Japanese fishing baskets and bait buckets carried by the tsunami. We learned that light items such as water bottles are driven by the wind while heavier items such as baskets float just under the surface and drift with currents rather than wind.

We removed approximately eight super sacks of debris from Dead Bird Beach, and Tom will collect the bags later this summer with a landing craft. (Super sacks are woven polypropylene bags, approximately 3′ x 3′ x 3′.) We labelled each bag with the appropriate two-mile segment, and NOAA and the Island Trails Network will analyze this data in the fall.

After a week, the winds shifted and intensified, so we moved to the calmer waters of the bay. We worked in teams of two which was sometimes creepy given the possibilities of bears. As we walked along the beaches, we sang out “Hey bear, Hey bear”, the best response being no response. At first glance, these inland shores seemed much cleaner, but we discovered how well the sand and logs camouflaged nets and ropes. In addition to being unsightly, nets pose a hazard to marine mammals, like seals, otters and whales.

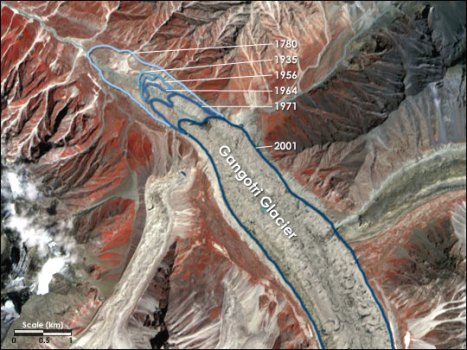

Tom warned us about the amounts of debris we would find on Shuyak Island, but it still surprised me that we found over ten thousand pounds of ropes, nets, and plastics in two weeks. No one lives there, and the island receives few visitors, so all the debris comes from somewhere else. I recalled reading Religious Studies scholar Kimberley Patton’s book The Sea Can Wash Away All Evils: Modern Marine Pollution and the Ancient Cathartic Ocean in which she explores the longtime human habit of throwing our waste into the sea. Perhaps it mattered less two thousand years ago, before people owned so much stuff.

Last February, I participated in Exxpedition, a sailing voyage on the 72′ Sea Dragon, assisting scientists investigating how disintegrating plastics disrupt the endocrine system. Exploring Shuyak Island in a 16′ kayak offered a different perspective, and I learned how larger plastics and debris migrate with wind and current. Nonetheless, the marine debris in both Alaska and the Caribbean primarily comes from somewhere else until it reaches that magical place called away.

On a cold rainy Sunday morning, the float plane brought our crew back to Kodiak and flew a new crew. As we flew away, I looked back at the super sacks on the beach and thought about what we had done. Overall, the trip gave me a terrific opportunity to spend time camping and paddling on a remote island in Alaska and to meet others who share these interests. But my experiences in the Caribbean and in Alaska have made me even more concerned about threats to our water, especially those at home in Florida. Perhaps, at one time, the sea washed away all evils, but today, the garbage we throw in the water comes back to haunt us.

Swimming and paddling in our springs feels like a gift, but seeing them through the eyes of new visitors makes me fall in love all over again. My friend Flo Turcotte, UF archivist for Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’ papers, detailed how Rawlings became enchanted by north central Florida’s primeval landscape in her article “

Swimming and paddling in our springs feels like a gift, but seeing them through the eyes of new visitors makes me fall in love all over again. My friend Flo Turcotte, UF archivist for Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’ papers, detailed how Rawlings became enchanted by north central Florida’s primeval landscape in her article “

On Saturday morning, April 2, 90+ kayakers and one paddle boarder (me) launched from

On Saturday morning, April 2, 90+ kayakers and one paddle boarder (me) launched from