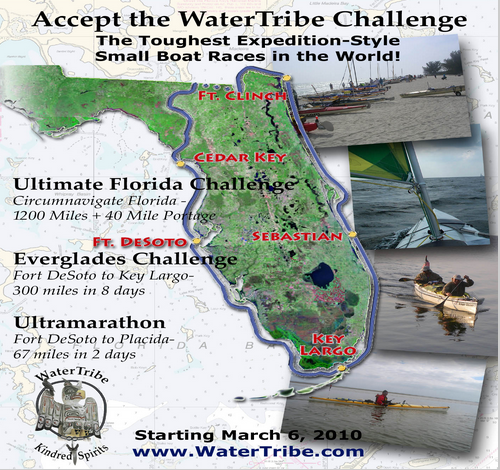

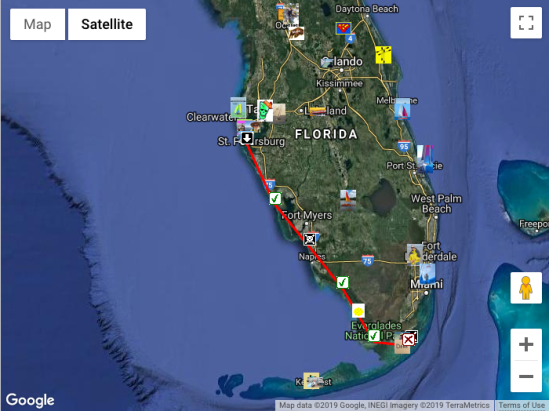

Can I paddle 300 miles in 7 days on a paddleboard? Do I want to attempt this feat? The WaterTribe Everglades Challenge is “an unsupported, expedition style adventure race for kayaks, canoes, and small boats” from Tampa to Key Largo, approximately 300 miles. The shorter Ultramarathan—the sprint version—extends the 67 miles from Tampa to Placida. The Watertribe blend of endurance, navigation, and expedition has tempted me ever since I first learned of this event. In January 2019, I attended the WaterTribe Boot Camp in Fort De Soto Park to see if I had the right stuff to enter the race in 2020.

The Boot Camp format consisted of a talk by Chief followed by a paddle and camping trip on Shell Island. Chief’s talk covered a range of topics critical for both starting and completing the challenge safely. A paddle or sail down Florida’s coast through the Everglades and Florida Bay is a serious undertaking. I already own and carry much of the safety gear based on my kayak training, but he reinforced the idea that critical gear should be carried on our bodies or PFDs. In my 5* BCU class, Gordon Brown emphasized the same point as we practiced on-water boat repairs. Chief’s mantra regarding GPS devices stuck with me: Two is one, and one is none, an accurate reflection of my experience with marine devices. Salt water and GPS’ do not play well together.

Chief also posed a question that each of us can only answer for ourselves. What are your goals in this challenge—to win your division or to finish? To me, finishing would be a victory. As Chief spoke, I did the math in my head. The event is almost 300 miles, and you have 8—really 7—days to get to Key Largo. The final party is in Key Largo on the 7th day, and I am not one to miss a party. That means approximately 45-50 miles per day. Can I handle the mileage and pace for 7 days straight? I have a year to figure that out.

My first challenge was finding a trail name. All long distance paddlers and hikers need a trail name. Through hikers on the AT and PCT have creative names, and I wanted a name that would also work for my upcoming AT hike. So I became Flamingo, and Janice chose HighTea in homage to her British heritage.

After Chief’s talk, the group headed to the beach where an array of boats and boards lined the shore. I was relieved to see another paddleboard there, but I was surprised to see so many sailing Hobies. I had assumed there would be more kayakers or canoers. One kayakers was incredulous when I revealed that I had a kayak at home. Why a paddleboard, he asked? I don’t think I can answer that, other than that I love the freedom of standing on a SUP.

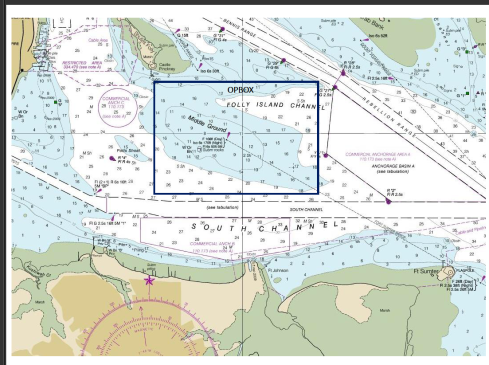

We launched from the boat ramp for the short paddle to Shell Key. Chief had sent us coordinates and waypoints for the campsite on Shell Key and for several paddling options. The Challenge itself leaves from a beach facing the Tampa Bay shipping channel, and crossing a shipping channel is always nerve-wracking. For the Boot Camp, the weather was sunny and warm, and the water glassy, but conditions are rarely that benign for the Challenge.

Plan A involved paddling through a mangrove tunnel, then through Bunce’s Pass to the outside of Shell Key. We paddled around a small island searching for the promised mangrove channel. We made it about 50 feet then realized it was a dead end. Since it was too narrow to turn around, we paddled backwards—fin first which might turn out to be a useful skill. On to Plan B, we crossed the shallow flats, passed the motorboats lining Bunce’s Pass, then headed north to find out campsite.

Our group camped midway up the beach. It’s hard to believe this level of wilderness camping exists so close to St. Pete and Tampa. I set up my 1-person tent that I bought for the Appalachian Trail. Packing like a backpacker is crucial to SUP expeditions. The weight must be balanced and centered. The Hobie Mirages might carry 80 pounds of gear, but I can only carry approximately 30 pounds, including water, on my board. One new tip: pool noodles. From now on, I’ll stow them in my gear bags to increase flotation in case of capsize. One of the best parts of the Boot Camp was picking up tips about gear and packing. The other part: the people.

The WaterTribe draws kindred spirits. After all, only so many people want to paddle from Tampa to Key Largo in any vessel, much less a paddleboard. After the sun set, we gathered around the campfire and traded stories. Though people came from all walks of life, it was a congenial and helpful group. I now understand why people come back year after year.

The next morning, I drank coffee as the sun rose, a luxury I might not have during the Challenge. To make miles, I assume that I’ll be on the water before dawn. Most people savored the slow morning and moved on to their own adventures by 10 am. Janice and I paddled around Mullet Key to see the launch site. As we headed back, the wind came up, a premonition of future conditions.

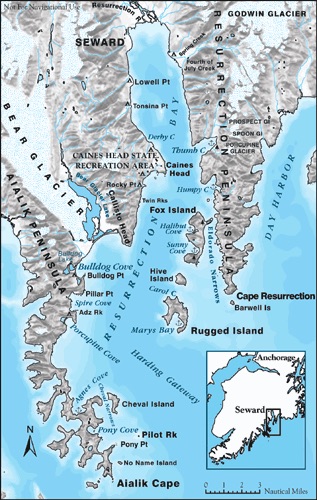

I have no doubt the Everglades Challenge will be difficult, probably one of the hardest things I will ever do. Between now and Challenge 2020, I’ll hike the Maine section of the AT and kayak Alaska’s Inside Passage which will prepare me. I’ll also train on the paddleboard and consider what size and length board will work best for me. I already know that my 12′ Fanatic is too slow. But I look forward to the next year of training, planning routes, and figuring out gear. Do I have the right stuff? I’ll never know unless I try.