I am sitting here at Susitna Place Bed and Breakfast in Anchorage, reflecting on our amazing run of clear and sunny weather. Denali is playing hide and seek, poking its head out from behind the few clouds that dot my horizon. Dawn, Kevin, and I are staying in Anchorage for a few days of r and r, relaxing after our Kachemak Bay paddling trip and gearing up for Shuyak Island.

We paddled along the Kachemak Bay Water Trail for one week, camping on beachfront campsites. although we had expected conditions that would let us play in tidal races and caves, the calm weather allowed us to bask in the beauty of the Alaskan waterscape.

The previous Sunday morning, Levi Hogan of Turnagain Kayak left the four of us, our boats,and a mountain of gear at Homer Spit. Homer Spit extends about six miles into Kachemak Bay, and from there, we could see almost all of our intended route. Our winds favorable, we launched into the calm waters of the Bay towards Gull Island, 2 1/2 miles across the Bay. A strong tailwind gave us a welcome assist, and small waves pushed our loaded boats towards our first campsite. After a quick nine mile paddle, we reached our campsite at Right Beach, our home for two nights. On our layover day at Right Beach, we explored Halibut Cove and the nearby islands. Humpback whales put on a whale show in front of our campsite.

Most of the Kachemak Bay Water Trail lies in the Kachemak Bay State Park, and the campsites and their amenities are clearly marked on the park map. Right Beach offered an outhouse and a water source, but the bear lockers excited us the most. Levi had given us bear canisters to hold our food, but the canisters proved to be Dawn- and Whitney-proof in addition to being bear proof. I stored my coffee in the bear vault over night, rightly surmising that fighting with the tabs on the canister BEFORE coffee would not work out well.

Two days later, under an overcast sky, we left Right Beach and headed for Kayak Beach, our home for three nights. We paddled past Halibut cove and Gull Island and around the point. As Kayak Beach came into view, we saw that the beach was full of tents and people, a surprise after the relative isolation of Right Beach. The several families present had been part of a larger group who camp there each year over the Memorial Day week. Over the years, they have created plumbing systems, a hot tub, and sophisticated cooking systems. They were just packing up to leave, and we wondered how they would fit the mountains of gear into their boats. These campers demonstrated what we have found to be Alaska generosity — they offered us water from their taps and home-smoked maple salmon.

Later that afternoon, two fisherman and their young sons came to stay in the campsite’s yurt. Most of the campsites have a yurt, complete with cots and wood stove. These fisherman too shared their bounty, giving us halibut, moose, and mussels. The two boys — about 8 and 11 — showed us how to collect mussels and cook them in sea water for flavor. They, too, were incredibly kind, but I wondered if they didn’t look at us with a bit of pity — like baby otters who couldn’t fend for themselves.

On our two layover days, we explored nearby coves and islands, first Tutka Bay, graced with waterfalls, and saw the salmon hatchery in Jakaloff Bay. Later, we paddled through the arch on Elephant Rock, just off the tip of Yukon Island, then down Sadie Cove, hoping for a glimpse of the rumored $5,000 per night lodge. The tidal range in Kachemak Bay is enormous, and our last night at Kayak Beach co-incided with one of the highest tides — 21.5 feet. On our last night there, Kevin woke us, shouting that our gear was floating away. We leapt out of our tents and dragged our gear to higher land. Sadly, the fire that we had cultivated for the past several days was lost to the sea.

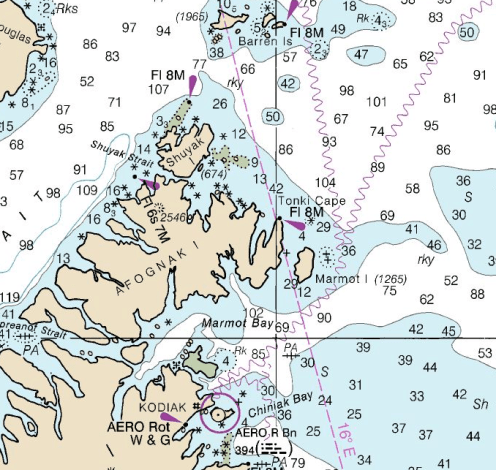

The seas were glassy for our 12.5 mile trip to Grey Cliff, just north of Seldovia. Seeing our reflections in the water seemed surreal, almost Dali-esque, as we paddled through this otherworldly-landscape. As we rounded the Seldovia headland, we finally found a play spot, a small tidal race where the out-going river flow met the incoming tide. What we call a tide race is labeled on our charts as ‘rip tide’. We surfed in the waves, then continued on to our campsite. Our Graycliffs campsite was in the Seldovia community park—we had passed out of the Kachemak Bay State park.

Soon after we arrived, a man drove up on an ATV—our ‘trail angel’. Gary told us about the park, drove us into town, and gave us a bottle of smoked salmon-flavored vodka, again demonstrating Alaskan generosity. Thus began the civilization part of our wilderness expedition. We ate, drank, and gorged on wi-fi. Friends had told us that the Kachemak Bay Water Trail was not a ‘wilderness’ trip, and our days in Seldovia proved that.

Back in Anchorage, looking at the calm waters of Cook Inlet and seeing Denali, I realize that we have had a remarkable weather window. While we have had few fun ‘conditions’ for play, we have had the luxury to fully be present in the sights and sounds of Alaska’s landscape. In several days, we fly to Kodiak and then on to Shuyak Island for the third leg of our trip. Who knows what the weather will bring, but whatever happens, I’m sure it will be interesting.

Swimming and paddling in our springs feels like a gift, but seeing them through the eyes of new visitors makes me fall in love all over again. My friend Flo Turcotte, UF archivist for Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’ papers, detailed how Rawlings became enchanted by north central Florida’s primeval landscape in her article “

Swimming and paddling in our springs feels like a gift, but seeing them through the eyes of new visitors makes me fall in love all over again. My friend Flo Turcotte, UF archivist for Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’ papers, detailed how Rawlings became enchanted by north central Florida’s primeval landscape in her article “

On Saturday morning, April 2, 90+ kayakers and one paddle boarder (me) launched from

On Saturday morning, April 2, 90+ kayakers and one paddle boarder (me) launched from

Twice last week, I swam in the blue waters of Cannon Springs. I brought my mask and snorkel so I could see the vent and the fish that swam in the hole. Even from the shore, I could see fish in the spring—the water was that clear. The entire Okhlawaha River is beautiful, but its hidden springs are gems that are worth working for. I had paddled south from the Payne’s Landing entrance and north from Eureka West to see the different moods of the river – the twisty s-turns closer to Eureka straighten out as the river widens on its northward course.

Twice last week, I swam in the blue waters of Cannon Springs. I brought my mask and snorkel so I could see the vent and the fish that swam in the hole. Even from the shore, I could see fish in the spring—the water was that clear. The entire Okhlawaha River is beautiful, but its hidden springs are gems that are worth working for. I had paddled south from the Payne’s Landing entrance and north from Eureka West to see the different moods of the river – the twisty s-turns closer to Eureka straighten out as the river widens on its northward course.

I had started to wonder if Cannon Springs and the Okhlawaha River was going to be my holy grail. Starting in September and lasting until March 2016, the Rodman reservoir on the Okhlawaha River is drawn down, the river-lake levels lowered substantially. This draw down occurs every few years—to prevent fish kills and reduce the vegetation that obstructs the water—and exposes the natural flow of the river. The lowered levels on the Okhlawaha River offer us a glimpse of the past and a future that could be—without the Rodman Dam. I was especially interested in seeing those springs like Cannon that reveal themselves only during these periodic drawdowns.

I had started to wonder if Cannon Springs and the Okhlawaha River was going to be my holy grail. Starting in September and lasting until March 2016, the Rodman reservoir on the Okhlawaha River is drawn down, the river-lake levels lowered substantially. This draw down occurs every few years—to prevent fish kills and reduce the vegetation that obstructs the water—and exposes the natural flow of the river. The lowered levels on the Okhlawaha River offer us a glimpse of the past and a future that could be—without the Rodman Dam. I was especially interested in seeing those springs like Cannon that reveal themselves only during these periodic drawdowns.

Finally, we spotted what had to be the entrance to Cannon Springs. Everyone said that the entrance to the Cannon Spring Run is unmistakable—a tree-lined corridor, and they were right.

Finally, we spotted what had to be the entrance to Cannon Springs. Everyone said that the entrance to the Cannon Spring Run is unmistakable—a tree-lined corridor, and they were right.

All of us are experienced wilderness paddlers, but we went with Don McCumber and Mike Akerman of

All of us are experienced wilderness paddlers, but we went with Don McCumber and Mike Akerman of  From Lulu Key, we paddled north, inward, first to West Pass, matching the shapes on our charts to the land masses we passed. We wove our way through passes and channels, all lined with mangroves. The subtly different shades of green alerted us to the narrow channels between islands.

From Lulu Key, we paddled north, inward, first to West Pass, matching the shapes on our charts to the land masses we passed. We wove our way through passes and channels, all lined with mangroves. The subtly different shades of green alerted us to the narrow channels between islands.

Inland, we found a small cemetery with headstones mostly from the Daniels and Anderson families. The islands hold other ruins but the ubiquitous mosquitos discouraged us from further exploration. Although there has been no official settlement on Fakahatchee Island for decades, the island shows evidence of recent habitation.

Inland, we found a small cemetery with headstones mostly from the Daniels and Anderson families. The islands hold other ruins but the ubiquitous mosquitos discouraged us from further exploration. Although there has been no official settlement on Fakahatchee Island for decades, the island shows evidence of recent habitation.