Originally posted on March 12, 2014 on Religion/Place/Pedagogy. After completing our exhibit—River of Dreams—on the St. Johns River at the Matheson History Museum, it seemed like a good time to repost this blog.

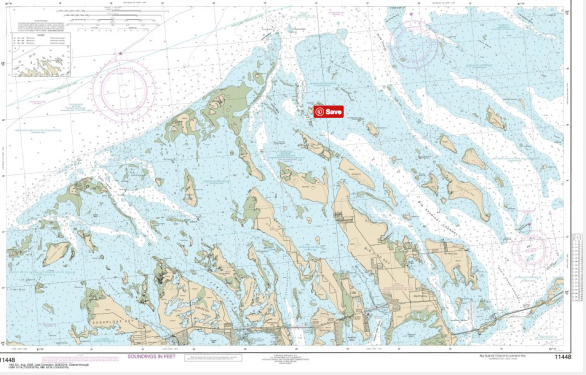

Nothing makes me happier than a day paddling through the waves in the Fort George Inlet. This estuary, just south of Little Talbot Island State Park, has become one of my favorite places to play in the surf, and this low country ecosystem, full of dolphins, pelicans, and hermit crabs, reminds me of Tybee Island, where I spent most of my childhood summers. I have camped at the Talbot House, a property recently deeded to the North Florida Land Trust. The house–and Big Talbot Island–sits in the Timucuan Preserve which includes both Talbot Islands, the Kingsley Plantation, the Fort Caroline National Monument as well as recently discovered burial native American mounds.

The house’s long dock extends into the marshy area of Mud Creek, a tributary of the Fort George Inlet, and from the dock, looking down the Mud River, I see the Kingsley Plantation on the opposite shore of the Fort George River.

Uncomfortable Histories

Seeing the Kingsley Plantation in the distance reminds me that I have a privileged history with this ecosystem. I have had the freedom to explore and discover the history, beauty, and wildlife on my own terms. The sixty or so slaves who worked the fields at the Kingsley Plantation did not have the luxury of appreciating the area’s beauty at their leisure. While I cannot even begin to imagine their experiences of the land, I know that our experiences are worlds apart. Perhaps the land—which has received their bodies, sweat, and blood—knows something more. Waves of residents, visitors, and invaders, from the Timucua followed by French and Spanish explorers and subsequent populations of British and Africans, have inhabited this land, drawn by its abundance and fertility as well as its strategic location. The Talbot Islands near Jacksonville, Florida are the southernmost of the Sea Islands and the region known as the Low Country–typically associated with the coasts of Georgia and South Carolina. The Low Country, so named for its extensive tidal flats and salt marshes, provides rich habitat for birds, fish, and mollusks, and its nutrient-rich mud sustained the human ecologies of rice-growing plantations.

From 1814 to 1837, Zephaniah Kingsley and his wife Anna, an ex-slave from Senegal, lived in what later became known as the Kingsley Plantation and produced commercial crops such as sea cotton and sugar cane. Also a slave trader, Zephaniah Kingsley participated in the Triangular trade, supplying human flesh to the barrier islands of Georgia and South Carolina. Like many, he sought out West Africans due to their agricultural skills, and there he purchased Anna who later became his wife.

Those of us who love Florida for its water and waves can easily forget our state’s uncomfortable histories. In 2013, Florida celebrated the 500th anniversary of Ponce de Leon’s arrival in what is now St. Augustine, approximately 50 miles south of the Timucuan Preserve. Over time, interactions with the Spanish, French, and later British newcomers decimated the Timucua populations, and only shell middens (trash piles of oyster shells and pottery, for example) and place names such as Timucua or Calusa remind us of their presence. Touring the Kingsley Plantation provides a visceral reminder of Florida’s participation in the slave trade, and the state’s Jim Crow laws maintained segregation and created a range of barriers in the post Civil War-era. In reality, these laws meant that beaches and rivers that I now enjoy were–and in some cases are–not safely accessible to people of color, and their experiences of these places might be radically different than mine.

Becoming Native to Place

When I teach courses such as Religion and Sustainability and Religion and Food at the University of Florida, I hope to make students aware of local places and their histories and ecosystems. Ideally, they will come to appreciate and maybe even love these places such as our estuaries, springs, and wild rivers. Many of my students, from a variety of backgrounds, already care deeply about our rivers, having grown up fishing, surfing, hunting, and swimming, and they are native to their place, to borrow Wes Jackson‘s term. Our students bring with them multiple histories and meanings about these places, and I need to reconcile my privilege–and that of many of my students–with the past and present exclusions experienced by others. Many outdoor areas were segregated by law and/or custom, and some of my students even today might not feel comfortable roaming through parts of rural north Florida.

I have never directly addressed this topic with students, although an artist friend and I have discussed creating a mapping project to explore different experiences of places. This mapping exercise might have two phases: first, students would learn the historical and ecological dynamics of this place; and, second, as a reflective piece, students would consider their own experiences of the encounter and how their experiences reflect larger social dynamics. I became interested in this idea after the two of us spent hours wandering through Koppers, our local super fund site, and, despite multiple ‘No Trespassing’ signs, nobody questioned us. In this case, the invisibility of white, middle-aged women was a privilege. In 2012, Michael W. Twitty, self-described culinary historian, historic interpreter and Jewish educator, embarked on a Southern Discomfort Tour through the Deep South to learn the stories of southern food ways, enslaved peoples, and cultural memories. During the tour’s visit to the Kingsley Plantation, he discussed the African’s cultural heritage and recreated some of their typical dishes.

Projects and exercise like Twitty’s Southern Discomfort Tour might provide a way to discuss the rich–and often uncomfortable–histories of places that I love. I hope my students will come to love our north Florida ecosystem and will learn to love whatever ecosystem that they inhabit in the future. I also hope they will acknowledge and appreciate that places also hold uncomfortable histories that continue to shape human and non-human relations in the present.

On December 28, we left our slip at

On December 28, we left our slip at