Early one morning in June 2019, I paddled my 16’ Pilgrim Expedition kayak through Skagway Harbor Marina, past rows of sailboats, fishing boats, and charters and finally beyond the cruise ships towards Lynn Canal. Skagway Harbor is the northern terminus of the Inside Passage, and our foursome—Dawn, David, Anthony, and myself—were beginning our 550 mile journey south to Prince Rupert, BC. We had risen at 4 am to beat the predicted afternoon winds, a routine we maintained for the entire journey. After months of packing, planning, and charting, we were finally on the road, southbound down the Alaska Marine Highway.

A Norwegian cruise ship had just arrived, and soon passengers would flood Skagway, buying t-shirts, jewelry, and raincoats. The previous night I watched a Disney cruise ship leave Skagway’s small harbor, tooting a familiar Disney melody to signal its departure. We passed the ferry terminal where the Alaska Ferry ‘Malaspina’ had carried us along with our boats and piles of gear. The thirty-eight hour ride—what some call the poor man’s cruise—previewed what we would see over the next month. For others, though, ferries are a lifeline and primary means of transportation. And here lies the reality and, perhaps, the beauty of the Inside Passage—cruise ships, ferries, and fishing boats also ply this swath of Alaskan wilderness.

“Whales every day,” Dawn had promised. True, few days passed without whale spouts or, even better, the fluke indicating the whale’s deep dive. Six weeks in Alaskan wilderness lured me, but so did the people and towns that populated Alaska’s Marine Highway, a segment of the Inside Passage. The Inside Passage is an approximately 1,000 mile route from Seattle, WA to Skagway, AK so named because the barrier islands buffer ocean swells from the Gulf of Alaska. The Inside Passage links people and places along southeast Alaska’s roadless coastal region, just as rivers served as highways throughout the lower 48 prior to roads. I embarked on this journey seeking adventure, but, in the end, my trip resembled a great American road trip, a mixture of crowds and solitude, rambling conversations and introspection.

Skagway’s crowded marina faded behind us, and the rocky shores of the mile-wide Lynn Canal surrounded us. Clear skies and glassy seas made our first day 15 mile paddle to Haines, Alaska a perfect shake-out day. For the first hour, the bear barrel in my cockpit cramped my legs, and I was grateful for our calm conditions. I had practiced cramming weeks of food, water, and gear into my boat again and again, but it still didn’t fit. At our first stop, I rearranged the barrel and other gear, a big improvement. Midway through the trip, I mailed home the bear barrel and other seemingly useless things—how could I still have too much stuff in the confines of a kayak?

A headwind made our last few miles into Haines difficult, no sooner than we paddled into the harbor the wind laid down. We pulled our boats onto the boat ramp and looked up towards the town. Southeast Alaska’s 12-18’ tidal range means that boat ramps are quite steep at low tide. The Harbormaster directed us to the nearby campground and pointed our carts to ferry our gear up the hill. No sooner than I had loaded a cart, a man called out “I’ve got a truck” and hauled our boats and gear to the campground. We wouldn’t have this luxury in our wilderness sites, but his kindness and a coin-operated shower crowned our first day. Harbormasters, shopkeepers, and random strangers—Alaskan hospitality is unparalleled. The harsh environment fosters both independence and interdependence because survival depends on relying on each other, a lesson paddlers learn well.

Skagway to Juneau: Headwinds on the Lynn Canal

By 6 am the following morning, we had packed, carried gear and kayaks down the ramp, and begun paddling south towards Juneau. Charts covered the decks of our kayaks, but navigating Skagway to Juneau is straightforward—follow the Lynn Canal south. The Lynn Canal is actually an inlet and considered the ‘Gateway to the Yukon.’ Over a hundred years ago, more than 100,000 prospectors traveled north up the Lynn Canal to stake a claim on the Klondike Gold fields. Many died, but many remained, transforming life in southeast Alaska forever. The Gold Rush began a population influx of North Americans and Russians into native populations, creating traumas and tensions that continue today.

We weren’t alone in the canal—cruise ships, fishing boats, and ferries motored past us. Cruise ships mostly passed in the late evening or early morning, often when we were getting ready for bed or packing up. I watched the boats as they passed, wondering what people were doing or if they even knew we were there. The ships seemed close but their wakes didn’t reach us until long after they passed. So many people in the canal, but we were so very alone.

The wind can be your friend or enemy in a canal. While preparing for the trip, we learned that the Inside Passage doesn’t have either northerly or southerly prevailing winds, so a fifty percent chance of headwinds on any given day. But, headwind or tailwind, a canal funnels wind. Leaving Haines, the winds increased to over 20 knots in our faces, and we crossed the mile-wide channel, hoping the canal might offer a windbreak. Headwinds and breaking waves made the crossing feel like paddling on a treadmill. The scenery never changed. We kept going—what choice did we have, and finally reached a beach on the tidal flats where glacial Katzehin River joins the Lynn Canal.

Our team had trained extensively in rough water, in coastal regions of the UK and the US, and the conditions were well within our skill sets. But Alaska’s remoteness and cold temperatures figure large in assessing risk so we decided to camp for the night. A rescue in these cold conditions would be dangerous. The cold water chilled us, even with our drysuits, and fleece layers, and my hands had become stiff with cold, even with paddling mitts. We got out of our boats to search for one of those campsites that had looked so inviting from afar. We sloshed upstream through ribbons of water snaking across the tidal flat, towing our boats with our safety lines. Finally, we reached a high point, above the presumed high tide line, and found a home for the night. Warm and dry, I didn’t let myself think about the bear tracks running through our site.

Every night, after dinner, I sat in my tent and listened to the weather report on my VHF radio. We were beyond cell phone reception. Knowing the wind direction and speed helped us plan the next day’s paddle. Most days we paddled between 20 and 25 miles, stopping for lunch and an occasional break. Paddling point to point rather than along shore cut our distance but made landings and breaks more difficult. Sometimes, I was so stiff by the time we stopped, I fell out of the boat into the water. I have never loved my drysuit more.

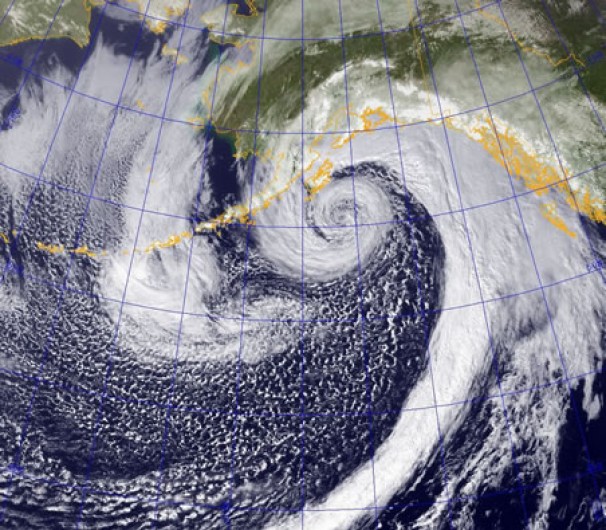

Several days beyond Haines and only a short distance from Juneau, our radios alerted us to a storm blowing up the canal, a storm fierce enough to warrant a weather day. We aimed for Bridget Cove, hoping to find refuge from the oncoming storm. Only a short distance by road from Juneau, Bridget Cove is a popular getaway spot. Another example of Alaskan hospitality, a man let us stay in Camp Freedom, a campsite and fire put area his son had built, and we rode out the storm in relative luxury. Only several days into the trip, I was starting to realize that people might be the highlight of our wilderness adventure. Looking back so many road trips and adventures, I remember the people I’ve met along the way.

Almost to Juneau, but first the Mendenhall flats, a mudscape impassable in anything other than high tide. Fortunately, Juneau’s tide peaked at noon so we reached the flats around 9:30 am to ride the tide to hot food and clean sheets. We paddled to the edge of the flats where the water diminished to a trickle. The navigational markers told us where the tide would flood, so we waited. And waited. Inch by inch, we muscled our boats down the slowly rising stream. High above us, small planes buzzed, carrying tourists to see Mendenhall Glacier, a sight we never saw. I knew Juneau was near, and my patience was wearing thin. The water rose enough to carry us, just barely, and our boats lurched forwards and backwards. We bumped the river’s edge and each other, as if the Three Stooges had possessed our boats. Bumper boats and warm showers in our near future, we laughed and laughed.

Juneau to Petersburg: Whales Tails, Bergie Bits and a Holey Boat

Clean sheets, a hot meal, and dry gear—I felt like a princess and a regular tourist. I bought stuff and shipped it home, toured museums, and drank too much wine. I walked the streets, upstream and down through throngs of disembarking cruise ship passengers. Surely some of these people had floated by our campsites, but miles of water and tons of steel no longer separated us. Now all of us crowded the streets, evaluating which attractions or stores merited a visit during our short time ashore.

Thirty-six hours later, we were ready to get back on the water and back to solitude. On a rainy Sunday morning, we perched on the floating docks at the Aurora Harbor Basin and crammed our gear, food, and water back into our boats. Even though we repacked daily, somehow the gear never fit the same way twice. My cockpit seemed suspiciously full of water, and after removing some gear, a small geyser erupted below my footpegs. My boat needed repair and fast. Everyone weighed in—the harbormaster, local sailors, and my team, until the marina hive mind arrived at a consensus: Flextape. I was skeptical. Petersburg, our next stop, lay over a hundred miles south. For the first several hours, I checked the repair obsessively, releasing my skirt to check for water. Only fiberglass and a strip of Flextape separated me from Alaskan waters. I continued checking over the next several days, but less frequently as I began to trust that my repair would hold. And it held until we reached Petersburg, where my boat received a proper repair.

We left Juneau and its crowded streets and joined the stream of marine traffic in Juneau’s harbor. We crossed the Gastineau Channel to avoid congestion, but a constant buzz alerted us to landing seaplanes. I’m used to looking left and right when crossing boat channels, but rarely up. I got used to it quickly—one more oddity that became the norm. Alaska’s coastline and roadless areas make seaplanes a vital part of transportation, and they, too, follow this marine highway.

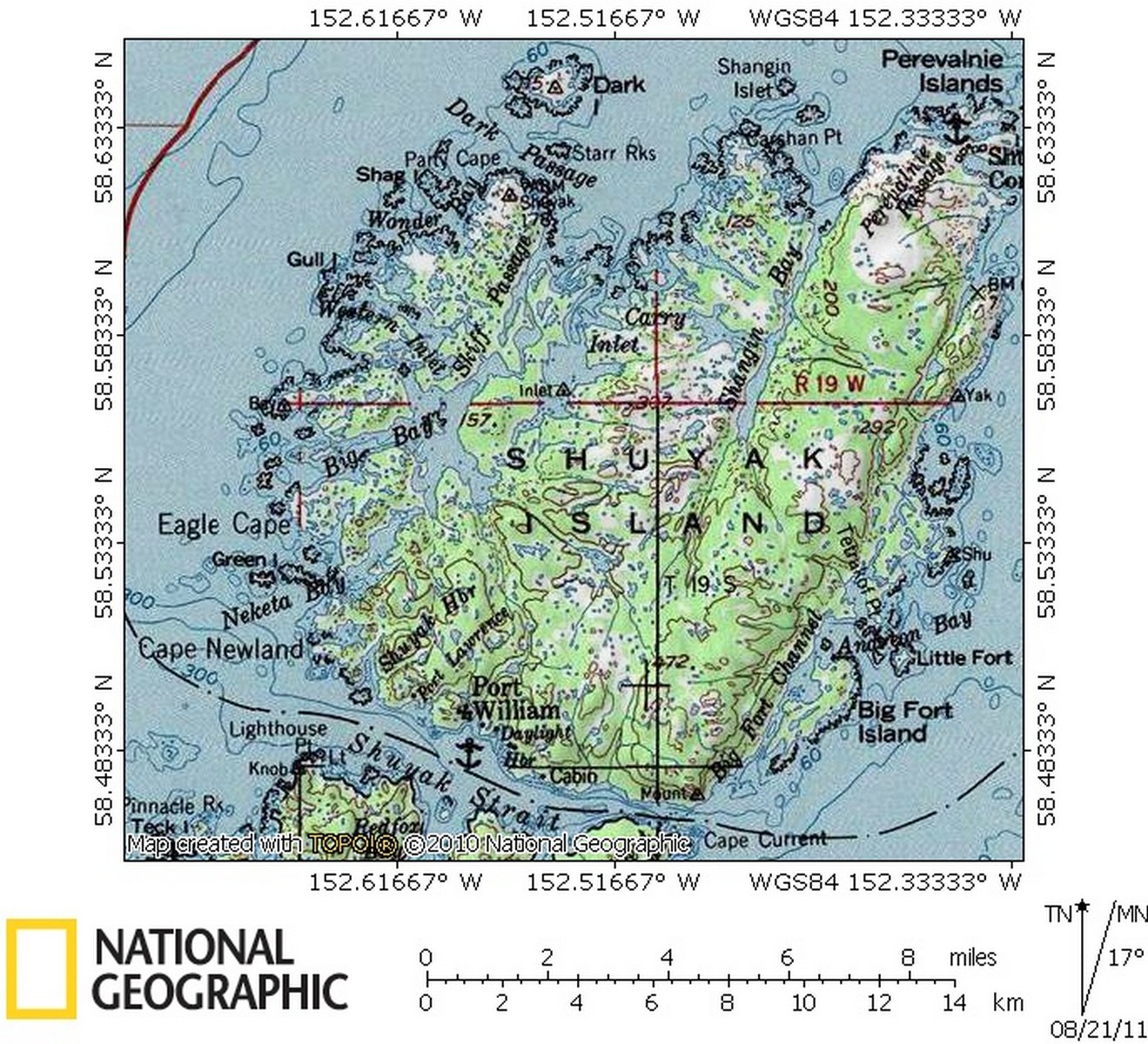

We continued south down the Lynn Canal, past Point Arden to the west and Bishop Point on right, and on past Slocum Inlet, Taku Harbor, Limestone Inlet, and Point Anmer. Each name represented a crossing, a point of interest, or a campsite. Months before, charts spread across my living room, I studied these sites and considered angles for crossing large and possibly treacherous inlets. Abstracted from the realities of wind, waves, and weather, these sites seemed mysterious, but they became embodied as the daily conditions dictated our paddling and camping.

The Juneau-Petersburg was the coldest and rainiest of the trip. Several nights during this leg, I woke up hungry in the middle of the night, but the thought of grizzlies killed any hope of a midnight snack. Day after day, we set up camp in the rain and broke camp in the rain. Nothing escaped the moisture. But one glorious evening, though, the sun emerged and stayed out just long enough to dry out gear and shake off the black sand from the previous night’s campsite. Dry clothes, dry bag, and dry tent—pure joy and a precious luxury! And even more fun, a young couple within weeks of completing the Inside Passage south to north joined us on our gravel beach. We traded stories and tips about upcoming highlights of our trips. The only fellow paddlers we met during our entire trip.

We continued south down the Lynn Canal, past Point Arden to the west and Bishop Point on right, and on past Slocum Inlet, Taku Harbor, Limestone Inlet, and Point Anmer. Each name represented a crossing, a point of interest, or a campsite. Months before, charts spread across my living room, I studied these sites and considered angles for crossing large and possibly treacherous inlets. Abstracted from the realities of wind, waves, and weather, these sites seemed mysterious, but they became embodied as the daily conditions dictated our paddling and camping.

The Juneau-Petersburg was the coldest and rainiest of the trip. Several nights during this leg, I woke up hungry in the middle of the night, but the thought of grizzlies killed any hope of a midnight snack. Day after day, we set up camp in the rain and broke camp in the rain. Nothing escaped the moisture. But one glorious evening, though, the sun emerged and stayed out just long enough to dry out gear and shake off the black sand from the previous night’s campsite. Dry clothes, dry bag, and dry tent—pure joy and a precious luxury! And even more fun, a young couple within weeks of completing the Inside Passage south to north joined us on our gravel beach. We traded stories and tips about upcoming highlights of our trips. The only fellow paddlers we met during our entire trip.

This rainy period also offered one of our trip’s greatest challenges—a foggy crossing of Tracy Arm in Stephens Passage. Denis Dwyer who has written extensively on the Inside Passage designates crossing Tracy Arm as a ‘crux move’ on the Inside Passage because cruise ships and tours enter this fjord to see whales and glaciers. Under any circumstance, crossings warrant caution: in addition to boat traffic, winds, tides, and currents create swell and potentially hazardous conditions. Fog adds another element of danger and beauty as well. Like most paddlers, we anticipated crossing in the mornings when winds tend to be low. Surprisingly, afternoons rains made the sea glassy, and we mostly crossed inlets and bays in the late afternoon. We deliberated briefly at Tracy Arm: go or no go. The fog was light enough to see any approaching ships, so we settled on our angle, checked compasses, and began paddling. We didn’t linger or chat during the crossing, but kept an eye out for ships and fog. Once across, we were relieved and without incident happy that we had completed one of our trip’s crux moves.

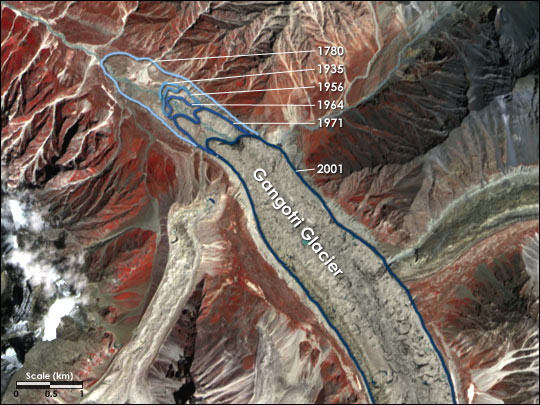

While we paddled down Stephens Passage past Tracy Arm, icebergs, or bergie bits, as many call them, took shape through the fog. The grey skies and fog made their eerie blue light even more dramatic. For the next several days, we tracked bergie bits as they moved miles and miles with the daily tidal flows. The bergie bits, along with the cruise ships, put the vastness of Alaska’s waterways in perspective: after paddling all day towards a ‘tiny’ bergie bit, I reached an ice mass that was indeed larger than my house.

Despite the cold and rain, this leg had few windy days which meant that we had plenty of time for sightseeing and thinking. Sometimes I chatted with Dawn, and we guessed cloud shapes. But mostly, we paddled on, lost in our own thoughts, and my mind wandered. I thought about my life in Florida, and what I wanted to do when I got back. Before the internet, before gadgets, I rode buses, trains, and planes, staring out the window, sometimes bored, sometimes thinking. This time helped me sort things out, and I returned home refreshed and with answers or new approaches to big questions in my life. More often now I scroll through my iPhone, and I wonder if the freedom to space out is a luxury that we have lost. The freedom of not being tethered or entertained.

These glassy seas also gave us the most whale sightings, or soundings. The sound of their spouts carried for miles, and we heard them before we saw them. After several, usually three, spouts, they breached, and, if we were lucky, we saw the tail as they dove deep. Stellar sea lions, otters, and seals also popped up. Seals, with their dog-like heads, popped up to watch us. Stellar sea lions, known to be aggressive, swam up behind us, revealed first by their heavy breathing. Sea kayaks don’t turn very fast, and the sound of heavy breathing right behind me always made me paddle faster.

One of my greatest fears was a close encounter with a bear, but we saw relatively few bears. The salmon were running late that year so the bears remained high in the mountains, eating berries. My Alaskan friends take bears in stride, just as Floridians co-exist with alligators and snakes, but I was happy that they stayed far away.

Our glassy seas enabled us to complete this leg faster than we anticipated. Even though we had trained for—and hoped for—more exciting conditions, too little is better than too much. We had all heard stories of trips gone bad. We reached Petersburg on a Friday morning, again excited for showers, food, and clean clothes.

Petersburg to Ketchikan: Highs, Lows and Mud Flats

A buoy covered with sea lions greeted us as we entered the Wrangell Narrows leading to Petersburg. Within an hour of arriving at the Petersburg marina, we had stored our gear, found lodging, and ordered fish sandwiches at Coastal Cold Storage, conveniently delivered to the Harbor Bar next door. My Pilgrim Expedition had been whisked away on a storage truck and reappeared Sunday morning, repaired by local kayaker Ken Hamilton. Even though I had stopped obsessing over the Flextape repair, a permanent repair was a huge relief. Such was my introduction to Petersburg, Alaska which—hands down—was my favorite stop on the marine highway.

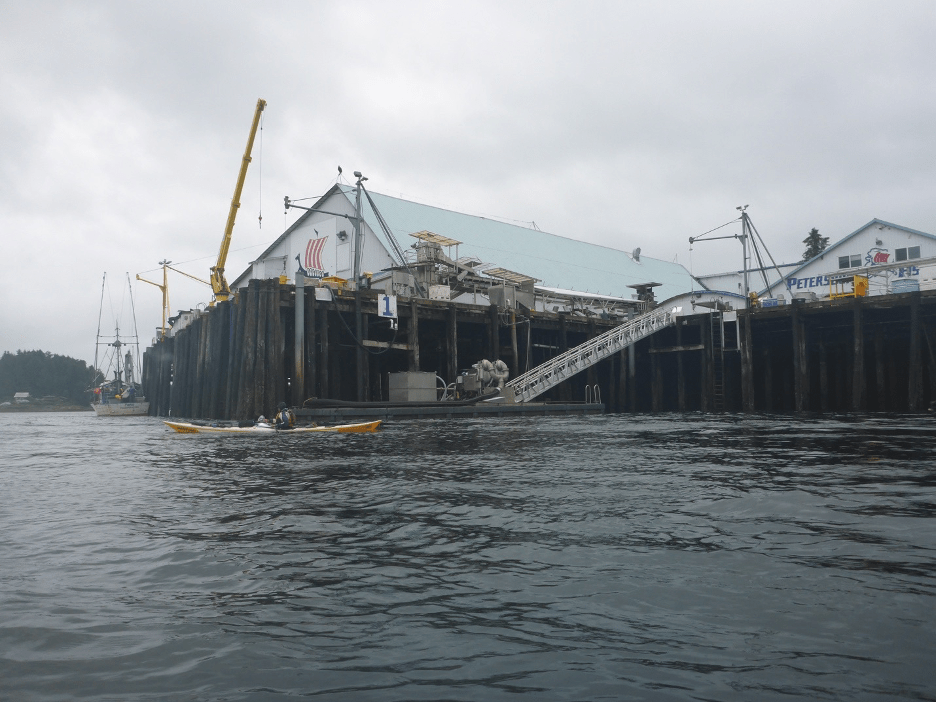

Fishing boats and processing plants dominated the harbor, not cruise ships. The stores catered to tourists but also local or seasonal residents who needed cold weather gear and other supplies. The streets and stores were calm enough that I had time to speak and joke with local residents. A friend’s daughter was moving temporarily to Petersburg, and that gave me an opening to ask about life there. I felt sure that she would enjoy her months living there.

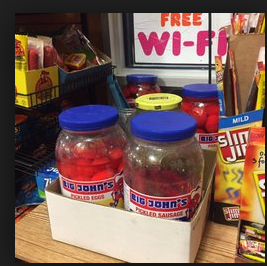

Again, cleaning myself, my clothing, and my gear dominated my time our shore leave, but I found time to visit almost every store on Petersburg’s main road, several of which allude to the town’s Norwegian heritage. We had missed the town’s Little Norway Festival which marks the start of the fishing season. My sense of adventure didn’t include trying the ‘Mystery Shots’ masked in brown paper bags at the Harbor Bar. The bartender told me that they mix random samples for these shots. I commented that my days of garbage can punch are long behind me.

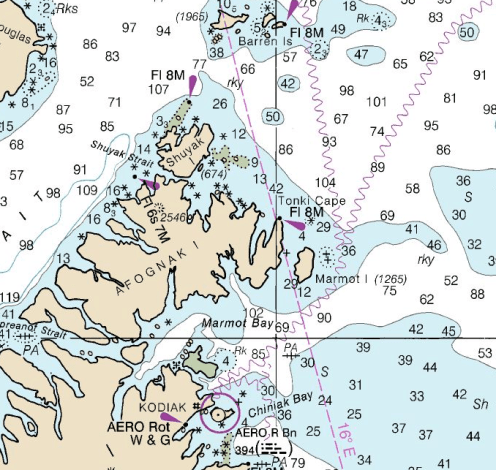

Sunday morning came quickly. We carted our gear back down to the back down the ramps to the floating docks. It was mid-tide so the ramps less steep. Nonetheless, I gripped the cart’s handle tightly, imagining the nightmare scenario of cart and gear flying down the ramp and into the water. Timing our actions to the tides was critical during the trip but especially so the next morning when we crossed Dry Straits, a large mudflat just north of Wrangell.

Early the next morning we paddled south and soon the outlines of the mudflats appeared. A 6:17 AM high tide meant we faced the flats during the ebb. We saw channels, and our charts showed channels, but even those began to run dry. One large channel remained, and if we didn’t reach that channel, we would be stuck on the flats for hours until the tide flooded back. The mud was firm, unlike much of Alaskan mud, so we pulled our kayaks across the mud toward the channel. Dragging a loaded kayak across mud is strenuous work—sometimes I walked pulling the tow rope over my shoulder, and other times I walked backwards. No-one complained—it was simply something we had to do, and a warm and sunny sky eased the pain. Wind and rain would have made a different story.

Timing tidal flows occupied a great deal of time and mental space. Alaska’s vast tidal ranges made choosing a campsite difficult and a chore that could take several hours. From the ferry going north, we spotted beautiful beaches, but later realized that many of these were submerged at high tide. Like Goldilocks, we needed the just right beach. Steep enough to remain above the tide line, and a bay deep enough to remain passable at low tide. Daily, we checked our tide charts and the kelp line that marked the previous tide.

After finding a site, we shuttled boats and gear to high ground, a task that could take over an hour, depending on the tide and the condition of the beach. A slippery rocky beach could produce a trip-ending ankle injury that might require an evacuation, so, in reality, the most dangerous part of the trip. Dawn had designed straps with handles so that the four of us could carry one boat at a time, standing upright rather than stooped over. We stepped carefully, aiming for the small bits of sand or dry rock that offered secure footing.

After Wrangell, we pointed south down Zimovia Strait into Ernest Sound and beyond the tiny community of Meyers Chuck into the vast Clarence Strait. Again, good weather allowed us to cover miles quickly, and soon we were two days out from Ketchikan. This leg proved to be the hottest, and each night, the sun beat down on us until it dipped below the horizon sometime after 10 PM. I lay in my tent sweating and finally understood the phrase ‘stewed in your own juices’.

Unable to sleep, I lay in my tent and reviewed charts, my GPS, and my Garmin Inreach, something I did most nights before bed. My Garmin Inreach was both a rescue lifeline and a means to send short, Twitter-length messages to my husband. Being outside of cell service and the internet was freeing, but I appreciated the contact with Kevin and the knowledge that my Inreach could summon help, in itself a freedom of sorts. My younger self backpacking in the 1970s might have scoffed at these gadgets, but my older self considers them a lifeline. I still have mixed feelings about being tethered, but overall the Inreach and the connections it offers me freedom to disappear into the wilderness yet remain connected to my husband.

We saw few cruise ships on this leg because we veered off the Alaska Marine Highway. I found that I missed the cruise ships and ferries which were conspicuous by their absence. That surprise me, but empty roads can be creepy when you expect to see people. Beyond Meyers Chuck, we merged back onto the Marine Highway and joined in the parade of boats and seaplanes coming and going from Ketchikan. Even though my daily experience of the Alaska Marine Highway was mostly wilderness, the boat traffic and the anonymous people on them played a big role in my experience. I enjoyed seeing those big boats every day and wondering about the people on them. Even if the connection with those passengers was remote and abstract, I savored the connection to other people.

Cruise ships and crowds would reappear in Ketchikan. On our last night before Ketchikan, we crossed the Behm Canal and camped on Pt. Higgins at the edge of the forest.

Ketchikan to Prince Rupert: Heading to Canada

Wind whistling through the trees woke me, and I knew immediately that our morning’s paddle down the Tsongas Narrows would be a slog. At some point overnight, grey skies obscured the previous evening’s warm sun, and I added an extra layer for warmth under my drysuit to prepare for the cold. Fighting the biggest headwind of the trip, we inched along, heads down, seeking windbreaks wherever possible.

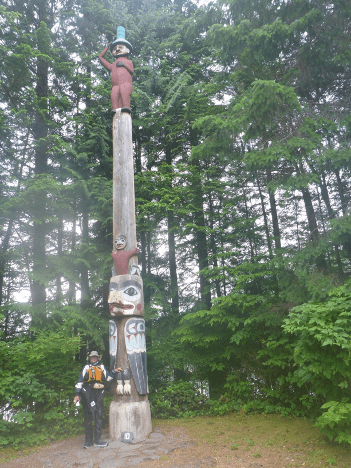

A small beach out of the wind led us to Totem Bight State Historical Park, which housed replicas of totem poles from the region. Dawn and I walked through the park to see the totem poles, while cruise ship passengers stared at us in our drysuits and PFDs. There was some irony about emerging from the wilderness to a museum that showcased a culture deeply entwined with the natural world. The totem poles and accompanying signs educate people about the First Nations people who inhabited the region prior to European contact. The rangers I spoke with were proud of their efforts in restoring totem poles and educating visitors. But, outside of museums and stores that sold native art, I wondered how native culture meshed with the dominant north American ethos. I wondered what this exhibit meant to cruise ship passengers and others whose Alaska voyage was shaped by buffets, casinos, and shopping.

We heard Ketchikan before we saw it, and we dodged seaplanes and boats as we paddled to our harbor. Ketchikan stretches out along the eastern side of the Tsongas Narrows waterfront, and its airport sits across the water on the west. A small ferry carries passengers back and forth. Perhaps because I stayed in a hotel across from the cruise ships, Ketchikan seemed louder than anywhere else. But this vantage point demonstrated the small town rhythms of Ketchikan. During the day, cruise ship passengers dominate the town, but, after 7 PM, after passengers reboard their ships, the residents emerge from their homes and shops. The sounds of crowds and shopkeepers entreating people to enter had disappeared. It was quiet. Locals strolled along the waterfront, and fisherman, lined the town’s creek, hoping for salmon to begin their run. The owner of one of the ubiquitous jewelry shops showed me her collection of native art and talked of life in Ketchikan. I told her of my kayak trip, and the next morning she photographed our departure and emailed the picture to me.

Prince Rupert, BC was calling. Three weeks of paddling, and we were within a week of completing a trip years in the making. Several large crossings remained, including the final crux move: Dixon Entrance, a large body of water open to swell from the Gulf of Alaska. But, weeks of paddling and multiple crossings behind me, my confidence had soared. I recalled our first day, the bear barrel crammed between my legs. Not an auspicious start. The logistics of getting ourselves, boats, and gear still loomed ahead. Dawn and I bought one-way tickets to Prince Rupert, not knowing how long the trip would take. David and Anthony drove gear and boats to Prince Rupert, and the question of ferry space back to the US nagged at them.

We continued south, accompanied by ferries and cruise ships, and our remaining days dwindled to three or four. On a gloriously sunny day, we stopped at the early hour of 3 PM to camp on a beach. This early day gave me a chance to savor our final days of the Alaskan wilderness. We assessed our site and the tide chart—the tidal range was over sixteen feet. We were near the Canadian border, and Alaska is one hour behind British Columbia. That night, at 2 AM, as the four of us stood, watching the tide creep towards our tents, wondering which time zone the tide obeyed. Fortunately the tide receded, but no-one slept much that night.

Our weather radios predicted a weather change, and by the next morning, winds and seas had risen. Not exactly desirable conditions for Dixon Entrance. We slogged across Observatory Inlet, fighting wind, tide, and current, another treadmill paddle. Once again, the scenery remained the same for hours, but we had no choice. Inch by inch, foot by foot, we made progress until we completed the crossing. Our reward—a pod of orcas played against the cliffs ahead of us!

Our goal that morning was Port Simpson or Lax Kw’alaams, BC, a small native community that we hoped would have cell service. It was time to scout options for our return home. Canadian charts and maps, I had noticed, included more native names than Alaskan charts. Just south of Dixon Entrance, for example, lies Haida Gwaii, that many know as Queen Charlotte Island. On our ferry ride north, a Tlingit crew member told us that many sites are now known by their first, or native, names, an important aspect of retaining cultural heritage.

Like many small communities in coastal Alaska and British Columbia, Port Simpson or Lax Kw’alaams relies upon ferry service. According to Google Maps, travel between the two towns requires both road and ferry. Even smaller routes are critical “roads” in a marine-based transportation system that provides access to necessary goods as well as medical care. But, in our port stops, I’d seen signs protesting imminent cuts to the ferries, and our ferry had already eliminated the bar service. Since then, ferry service on the Alaska Marine Highway has been drastically reduced, affecting residents and adventurers alike.

Prince Rupert: The End of the Road

We landed at the Cow Bay Marina in Prince Rupert. After a celebratory ice cream bar at the gift shop, we focused on our chores—unloading our boats, Canadian customs, and cleaning up. I had wondered if we wouldn’t all give a big whoop when we finished. Looking back, perhaps smaller, and more significant, insights and burst of joy replaced that big whoop. Perhaps, this the end of this journey was too much to take in all at once. We had excitement for sure, whales, wind, and seals, and glimpsed life in the few exits along the Alaska Marine Highway. And this wilderness highway spared me billboards like the incessant “South of the Border” signs on I-95 that I loved as a child. But the time and space to think and dream that bored me as a child now felt like a paddling meditation. And this might have been the great gift I received: the time to simply be.

This trip illustrated some realities of scientific data collection and helped me reflect on my own research methods, which have been primarily ethnographic. By training, I am an historian of religion, and I study both texts and people. I have done ethnographic research, for example, interviews and participation-observation in different communities. To collect data for my projects, I have

This trip illustrated some realities of scientific data collection and helped me reflect on my own research methods, which have been primarily ethnographic. By training, I am an historian of religion, and I study both texts and people. I have done ethnographic research, for example, interviews and participation-observation in different communities. To collect data for my projects, I have